Construction sector:

Issues in information

provision, enforcement

of labour mobility

law, social security

coordination regulations,

and cooperation between

Member States

2023 | ELA Strategic Analysis

#EULabourAuthority

Construction

sector: Issues in

information provision,

enforcement of labour

mobility law, social

security coordination

regulations, and

cooperation between

Member States

2023 | ELA Strategic Analysis

The present document has been produced by Milieu Consulting SRL and Eftheia as authors. This task has been carried out exclusively by the authors in the context of a contract

between the European Labour Authority and the authors, awarded following a tender procedure. The document has been prepared for the European Labour Authority, however it

reects the views of the authors only. The information contained in this report does not reect the views or the ocial position of the European Labour Authority.

Disclaimer: This report has no legal value but is of informative nature only. The information is provided without any guarantees, conditions or warranties as to its completeness or accuracy. ELA

accepts no responsibility or liability whatsoever with regard to the information contained in the che nor can ELA be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information.

This information is: of a general nature only and not intended to address the specic circumstances of any particular individual or entity; not necessarily comprehensive, complete,

accurate or up to date; sometimes linked to external sites over which ELA has no control and for which ELA assumes no responsibility; not professional or legal advice.

For further information please contact the competent national authorities.

Neither the European Labour Authority nor any person acting on behalf of the European Labour Authority is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information.

Luxembourg: Publications Oce of the European Union, 2023

© European Labour Authority, 2023

Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.

For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that are not owned by the European Labour Authority (ELA), permission may need to be sought directly from the respective rightholders.

Cover photo: © AdobeStock_143621122

PDF: ISBN 978-92-9401-399-6 doi:10.2883/9750 HP-09-23-367-EN-N

3

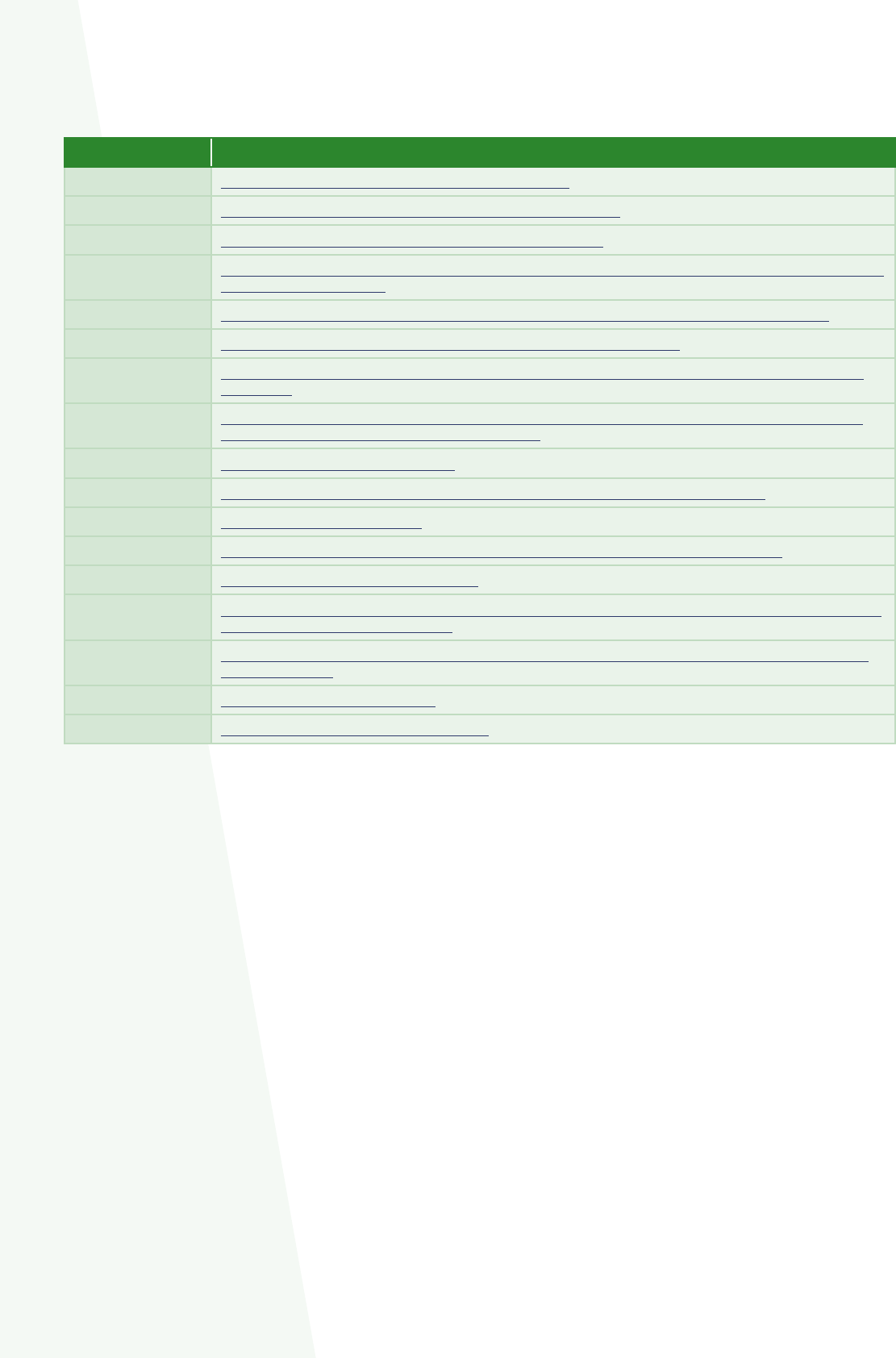

Contents

List of abbreviations ....................................................................................................................................................................6

Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................................................7

Executive summary .....................................................................................................................................................................8

1. Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................................................9

2. The construction sector: Key characteristics and challenges .............................................................................. 11

2.1 The construction sector in the EU economy .................................................................................................... 12

2.2 Subcontracting and the role of temporary work agencies ......................................................................... 13

2.3 Posted workers and key mobility patterns ....................................................................................................... 15

2.3.1 Data from portable documents A1 ........................................................................................................ 16

2.3.2 Data from prior declaration tools and micro-data ............................................................................ 19

2.3.2.1 Austria .............................................................................................................................................. 20

2.3.2.2 Belgium ........................................................................................................................................... 20

2.3.2.3 France .............................................................................................................................................. 21

2.3.2.4 Germany ......................................................................................................................................... 21

2.3.2.5 Italy ................................................................................................................................................... 21

2.3.2.6 Luxembourg .................................................................................................................................. 22

2.3.2.7 The Netherlands ........................................................................................................................... 22

2.3.2.8 Poland .............................................................................................................................................. 23

2.3.2.9 Slovenia ........................................................................................................................................... 23

2.3.2.10 Spain ................................................................................................................................................. 23

2.3.2.11 Other Member States ................................................................................................................. 24

2.4 Intra-EU posting of TCNs in the construction sector ..................................................................................... 24

2.5 Abusive practices in the context of the posting of workers in the construction sector ................... 25

Letterbox companies in sending countries ...................................................................................................... 25

Fake posting by means of permanent/rotating posting ............................................................................. 25

Bogus self-employment ........................................................................................................................................... 26

Overtime and underpayment as non-respect of working conditions .................................................... 26

Fraudulent PD A1 form ............................................................................................................................................. 26

Illegal employment of TCNs or fraudulent posting of TCNs ....................................................................... 26

3. Information needs of workers and employers and measures to address them ........................................... 28

3.1 Legal framework on information and relevant tools and actors .............................................................. 29

3.2 Information needs ...................................................................................................................................................... 34

3.3 Suggested way forward to better inform posted workers and their employers in the

construction sector .................................................................................................................................................... 35

4. Preventive measures .......................................................................................................................................................... 38

4.1 The role of social ID cards in the EU construction sector ............................................................................. 39

4.2 Subcontracting chain liability schemes in the EU construction sector .................................................. 41

4.3 Limits on subcontracting to improve the implementation of liability schemes ................................. 45

4.4 The role of public procurement in the compliance with EU labour mobility rules applying

to posted workers in the construction sector .................................................................................................. 45

4

4.5 Portable Documents A1: the administrative tie of the EU social security coordination................... 47

4.5.1 Legal framework ........................................................................................................................................... 47

4.5.2 Gaps and criticalities relating to portable documents A1 ............................................................. 48

4.6 Prior declaration tools .............................................................................................................................................. 49

5. Enforcing EU labour mobility and social security rules in the EU construction sector .............................. 52

5.1 Challenges in the enforcement of EU labour mobility and social security rules in the EU

construction sector .................................................................................................................................................... 53

5.2 Sanctioning mechanisms ........................................................................................................................................ 56

5.3 Resources allocated to labour inspectors and inspection tools ................................................................ 57

5.4 Cross-border cooperation between social security and enforcement institutions ........................... 58

5.5 The role of trade unions in supporting the enforcement of posted workers’ rights in the

construction sector .................................................................................................................................................... 60

5.6 Conclusions on enforcement ................................................................................................................................. 62

6. Cross-border matching initiatives to address labour market imbalances in the EU construction

sector........................................................................................................................................................................................ 63

6.1 Introduction and context ........................................................................................................................................ 63

6.2 Trends and state of the art ...................................................................................................................................... 65

6.3 The impact of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine on labour market imbalances in

the EU construction sector ...................................................................................................................................... 66

6.4 Cross-border matching/recruitment initiatives to address labour market imbalances in the

EU construction sector ............................................................................................................................................. 67

6.5 Conclusions .................................................................................................................................................................. 71

7. Operational conclusions ................................................................................................................................................... 72

1. Information provision ............................................................................................................................................... 72

2. Concerted and joint inspections ........................................................................................................................... 72

3. Cooperation between Member States ............................................................................................................... 73

4. Data collection ............................................................................................................................................................ 73

Bibliography ................................................................................................................................................................................ 74

EU documents ...................................................................................................................................................................... 78

Annex1– Interviews ................................................................................................................................................................ 79

Annex2– Case study interviews ......................................................................................................................................... 81

Annex3– Single ocial national websites ..................................................................................................................... 83

Annex4– Bilateral agreements between Poland and other Member States ..................................................... 84

5

List of tables

Table1: Case studies overview ............................................................................................................................................ 10

Table2: Roles and responsibilities of the contracting business and temporary work agency ..................... 14

Table3: Main receiving/sending Member States of postings in the construction sector, based on

PDs A1 issued under Article 12, 2021. .......................................................................................................................... 17

Table4: Member States where construction is the primary sector for incoming/outgoing posted

workers, 2021 ........................................................................................................................................................................ 18

Table5: Main corridors of postings in the construction sector between Member States, 2021 .................. 18

Table6: Posted workers in the construction sector as a share of total employment according to

Art. 12 PDs A1 data, 2021 .................................................................................................................................................. 19

Table7: Typology of abusive practices in the construction sector ......................................................................... 27

Table8: Overview of the dierent social ID cards in the 17 Member States covered in this study ............. 39

Table9: National measures on subcontracting liability in the construction sector in force in the17

Member States covered under this study according to the Commission Communication on the

implementation of Directive 2014/67/EU .................................................................................................................. 43

Table10: Typology of measures and examples of countries .................................................................................... 68

List of boxes

Box1: Case study on construction companies’ initiatives to inform posted workers in the

construction sector in sending and receiving Member States ........................................................................... 29

Box2: Case study on the role of social partners in provision of information to workers and employers . 32

Box3: Case study on employer practices in accessing information ....................................................................... 36

Box4: Case study on the role of public procurement in compliance with EU labour mobility rules

applying to posted workers in the construction sector. ...................................................................................... 46

Box5: Case study on labour inspectorates’ access to databases ............................................................................. 50

Box6: Case study on good practices and key issues in enforcement by labour inspectorates of

labour mobility rules and social security coordination regulations.................................................................. 54

Box7: Case study on bilateral agreements between Poland and receiving Member States ........................ 59

Box8: Case study on the enforcement of workers’ rights in sending Member States .................................... 61

Box9: Ukrainians in the Polish construction sector ...................................................................................................... 66

Box10: Initiatives targeting TCNs........................................................................................................................................ 70

List of gures

Figure1: Number of employed and growth rate of employment (in%) in the construction sector,

2021 .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 12

Figure2: Temporary work agency workers in the construction sector (% of total employees), 2021 ....... 14

Figure3: Causes of quantitative and qualitative shortages....................................................................................... 64

Figure4: Example of factors creating imbalances in the construction sector .................................................... 65

6

List of abbreviations

BUAK Bauarbeiter-Urlaubs- und Abfertigungskasse [Construction Workers’ Annual Leave and Severance Pay Fund]

Cedefop Centre for the Development of Vocational Training

CJEU Court of Justice of the European Union

CNV Christelijk Nationaal Vakverbond [Christian National Trade Union Federation]

ECSO European Construction Sector Observatory

EFBWW European Federation of Building and Woodworkers

EFTA European Free Trade Association

ELA European Labour Authority

ETUC European Trade Union Confederation

EU European Union

EU-BCS European Business and Consumer Surveys

EURES European Employment Services

EGD European Green Deal

FIEC European Construction Industry Federation

FNV Federatie Nederlandse Vakbeweging [Federation of Dutch Trade Unions]

GVA Gross value added

ILO International Labour Organisation

IMI Internal Market Information System

ISCED International Standard Classication of Education

Limosa Cross-Country Information System for Migration Research at the Social Administration

OSH Occupational safety and health

PD A1 Portable Document A1

PDT Prior declaration tool

PROMO Protecting Mobility through Improving Labour Rights Enforcement project

SME Small and medium-sized enterprise

SOKA BAU Sozialkassen der Bauwirtschaft

TCN Third Country National

Urssaf Unions de recouvrement des cotisations de sécurité sociale et d’allocations familiales [Organisations for the

Collection of Social Security and Family Benet Contributions]

UWV Uitvoeringsinstituut Werknemersverzekeringen [Institute for Employee Insurance]

7

Abstract

This study analyses challenges related to the enforcement of labour mobility and social security laws in the construction

sector, with a specic focus on the posting of workers. Despite measures in place in the European Union Member States to

ensure compliance with posting rules, their enforcement has been challenging in the construction sector. Posted workers

and their employers are also not always fully aware of their rights and obligations despite several initiatives to improve

the communication of relevant information by social partners, Member States and the European Commission. The sector

also struggles with labour and skill shortages, and although some cross-border initiatives exist to address these shortages,

they are often hindered by language and cultural dierences, along with limited recognition of skills and qualications.

The ndings in this study suggest that the European Labour Authority (ELA) could play a more active role in supporting the

improved enforcement of posting rules in the construction sector in Member States, the communication of information

to workers and employers concerned, and contributing to the improvement of data collection on labour mobility in the

construction sector.

The ELA Strategic Analysis series keeps track of emerging trends, challenges and loopholes in the areas of labour mobility

and social security coordination. It includes in-depth analyses and studies that investigate specic issues, recurring

problems and sector-specic challenges. The analyses contribute to risk assessment to inform ELA’s operational activities as

well as the work of national competent authorities, and, where appropriate, the social partners.

8

Executive summary

This report addresses challenges related to the enforcement of labour mobility and social security law in the construction

sector, with a focus on the posting of workers. It is based on the review of literature, statistical analysis and empirical work in

Member States most aected by labour mobility in the construction sector that was conducted between October 2022 and

May 2023.

The construction sector plays a vital role in the EU economy, employing approximately 13million people and contributing

around 5.5% to the gross value added (GVA). In 2021, around one in four portable documents A1 (PDs A1) issued was

granted for services in the EU construction sector. This amounts to an approximate estimate of 833000 PDs A1 issued in

the sector. Germany was the primary receiving country for posted workers in the EU construction sector, while Poland was

the main sending country. The 2021 gures indicated a recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic in most Member States as

far as the number of postings was concerned. A relatively high rate of third country nationals (TCNs) are employed in the

EU construction sector and posted to other Member States than their own Member State of residence. These TCNs face

some specic challenges compared to other posted workers, such as dependence on employers for work permits, language

barriers, irregular employment, non-payment of social contributions and more exposure to occupational health and safety

risks.

The enforcement of legislation on the posting of workers in the construction sector poses several challenges. The most

prevalent violations and abusive practices include the establishment of letterbox companies, non-compliance with working

conditions, bogus self-employment, fraudulent PD A1 usage and fraudulent posting of TCNs. Labour inspectorates have the

necessary inspection and sanctioning regulatory tools to address these violations and abusive practices, but lack sucient

nancial and sta resources, and experience diculties in identifying some factual elements in such posting contexts (e.g.

place of registration of undertakings, number of contracts performed, whether or not the posted workers return to or are

expected to resume working in the sending Member State) to properly carry out their inspection activities. Furthermore, the

imposition of sanctions and their eective implementation can be dicult in a cross-border situation.

The report identies several relevant measures to prevent non-compliance with posting rules in the construction sector.

These include social ID cards, subcontracting chain liability schemes, limitations on subcontracting and specic public

procurement rules. The Member States, together with social partners and the European Commission, also launched several

measures to better diuse information to workers and employers about their rights and obligations in a posting context.

Despite these measures, workers and employers in the construction sector are still not considered to be well informed.

Moreover, major deciencies in the communication tools and methods were agged, leading to confusion and diculty

in accessing relevant information. These shortcomings included a use of complex legal language, lack of translations, and

scattered sources of information.

The EU construction sector is also facing signicant labour and skill shortages. To address such shortages, Member States

have implemented various cross-border initiatives, including enhancing skills development, oering training opportunities

and fostering cross-border cooperation. Several initiatives are also targeted at the recruitment of TCNs, often through

bilateral agreements with third countries.

Based on the ndings of this study and taking ELA’s mandate into consideration, some operational conclusions have been

drawn. These conclusions highlight the need for more support from ELA to improve the enforcement of posting rules within

Member States in the construction sector, to better communicate information at the EU and Member State level to workers

and employers in the construction sector, and to contribute to the improvement of data collection on labour mobility in the

construction sector.

9

1. Introduction

The construction sector in the European Union directly employs around 13million people and is an essential part of its

economy. The EU construction sector has experienced persistent labour and skill shortages over the years along with

signicant worker mobility ows between Member States, in particular from eastern to western Member States. These

shortages are often eased through the posting of workers. Due to its characteristics, notably the prevalence of complex and

labour-intensive projects relying on subcontracting chains, the construction sector is more susceptible to abusive practices

that lead to infringements of the EU legal framework on labour mobility and social security coordination.

The European Labour Authority (ELA), which plays an essential role in facilitating and enhancing cooperation between

Member States to help ensure that EU rules on labour mobility and social security coordination are enforced, selected the

construction sector as one of its priorities for 2023.

Within this context, this study aims to assist ELA and Member States in addressing challenges arising in the construction

sector relating to the enforcement of labour and social security law (such as information exchange and cooperation). The

study focuses primarily on the posting of workers in the construction sector. It provides an overview of the construction

sector labour market and its key characteristics, including a detailed analysis of the number of posted workers in the

construction sector and key mobility patterns (Section2). It maps the information needs of posted workers and employers

and the measures taken to address these needs (Section3). It analyses measures in place to prevent infringement of EU

mobility rules in the construction sector (Section4) and explains how these rules are enforced in Member States sending

and receiving posted workers (Section5). The study also outlines cross-border matching initiatives to address labour and

skill shortages in the EU construction sector (Section6). Finally, based on the ndings in these sections, the study develops

operational conclusions, taking ELA’s mandate into account (Section7).

This study is based on the following ve main research streams carried out between October 2022 and May 2023.

• A comprehensive review of the literature including peer-reviewed articles, conference papers and reports from

representatives of social partners at the EU level were mapped, selected and analysed. The review considered literature in

English, prioritising the literature covering the period from 2014 onwards.

• A quantitative data analysis showing key mobility patterns in the construction sector with a focus on 2019–2021, using

the European Commission’s annual reports on portable documents A1 (PDs A1) and the POSTING.STAT project from

HIVA– Research Institute for Work and Society KU Leuven as the main data sources.

• Seven exploratory interviews with selected stakeholders to better understand the situation of posted workers in the

construction sector and the issues at stake (e.g. challenges in the enforcement of EU labour mobility legislation in the

construction sector). See Annex1 for the full list of interviewees.

• 21 interviews with either a representative of a central inspection authority or another relevant stakeholder in

the 17 main sending countries (Czechia, Germany, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia and Slovakia)

and receiving countries (Belgium, Germany, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Austria, Finland and Sweden) of posted

workers in the construction sector. Interviewees were identied in cooperation with ELA national liaison ocers. The

interviews covered the information needs of these workers and their employers, the challenges linked to the application

and enforcement of EU labour mobility rules in the construction sector, and the identication of cross-border matching/

recruitment initiatives of public authorities or social partners to address labour and skill shortages in the construction

sector. They also focused on good practices(

1

) and areas for improvement under these three aspects.

• 10 case studies covering selected Member States(

2

) that receive posted workers in the construction sector, namely

Belgium, Germany(

3

), France, the Netherlands and Austria, and Member States that posted workers in the construction

sector, namely Germany, Croatia, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia and Slovakia, based on interviews with key actors (i.e. social

partners, labour inspectorates, labour court representatives and authorities in charge of public procurement). The 10 case

studies are detailed in the table below. The case studies were selected in cooperation with national liaison ocers and

based on the preliminary ndings of the study. Their aim was to provide an in-depth understanding of the situation of

posted workers in the construction sector in relevant Member States.

(

1

) Good practices to be defined according to ELA criteria: https://www.ela.europa.eu/en/call-good-practices-2022#bcl-inpage-item-780.

(

2

) These countries were selected based on available information on the total number of PDs A1 issued under Article 12 of Regulation (EU)

2018/1139 (the Basic Regulation). As a result, certain Member States where construction is a highly significant sector among posted workers

(e.g. Estonia and Romania) may be excluded from this list.

(

3

) Germany is covered both as a receiving country and as a sending country.

10

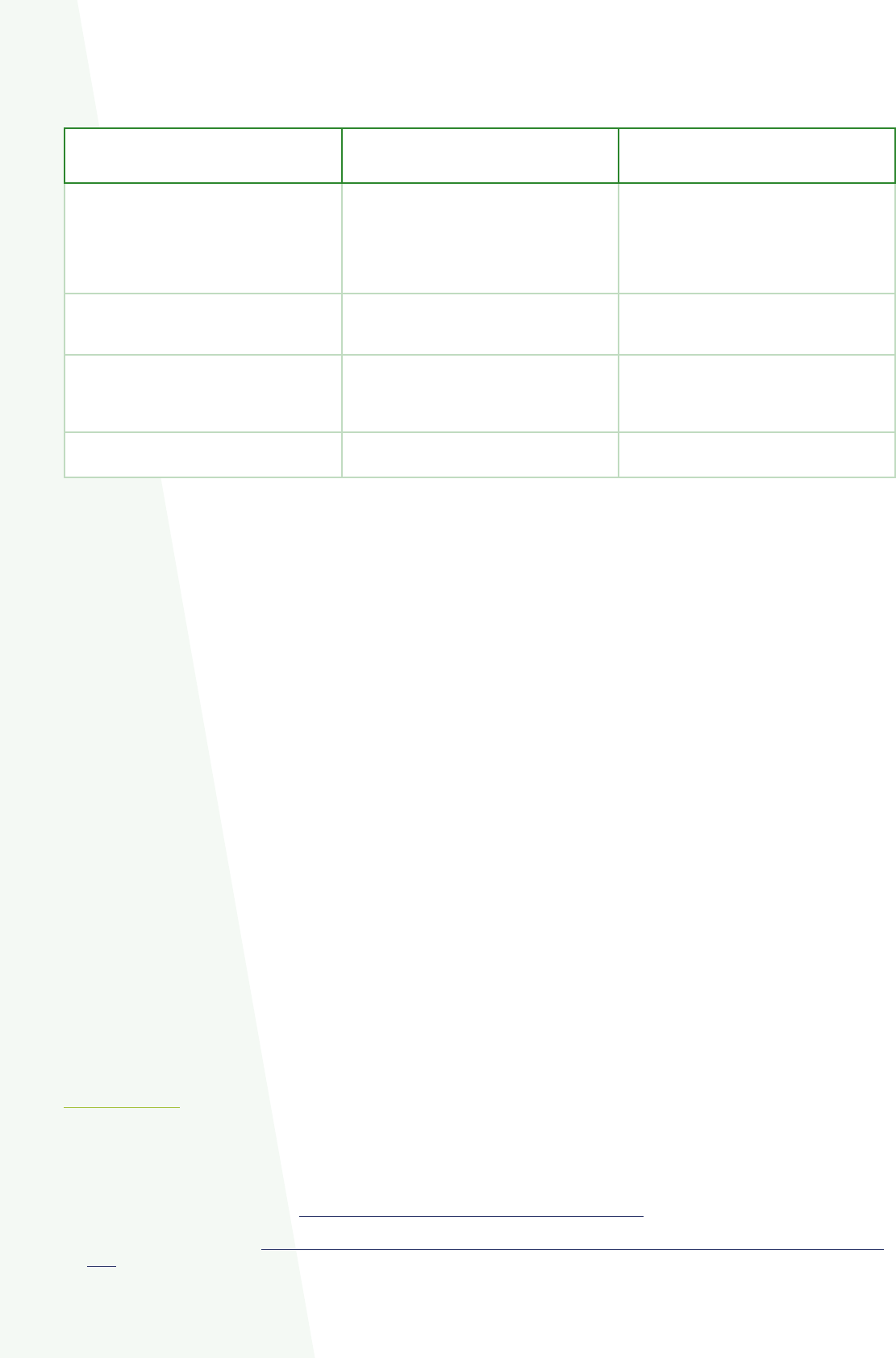

Table1: Case studies overview

Case studies

Sending Member State Receiving Member State

HR PL PT SI SK BE DE FR NL AT

Construction companies’ initiatives

to inform posted workers in the

construction sector in sending and

receiving Member States

X X X X X X X X X X

Employers’ practices in accessing

information

X X X X X X X X X X

The role of social partners in provision

of information to workers and

employers

X X X X X X X X X X

Good practices and key issues in

enforcement by labour inspectorates

of labour mobility rules and social

security coordination regulations

X X X X X

Labour inspectors’ access to other

databases to cross-check data (e.g. PD

A1, tax records)

X X X X X

Public procurement in compliance with

EU labour mobility rules applying to

posted workers in the construction

sector

X X X X X

Enforcement of workers’ rights in

sending countries

X X X X X

Bilateral agreements between Poland

and receiving Member States

X X X X X X

Cross-border matching/recruitment

initiatives to address labour and skills

shortages in the construction sector

X X X X X X X X X X

Chain liability and posted workers

in subcontracting schemes in the

construction sector

X X X X X

The methodology for this study was designed to be feasible, considering its scope and timeline and the sources of

information available. Therefore, the ndings under this study must be read considering the following limitations.

• The study covers 17 Member States.

• Case studies cover 10 Member States.

• Posted workers and employers were not directly consulted; instead, their representatives (i.e. social partners) were

interviewed.

• There is limited up-to-date academic literature and quality data on some of the topics discussed. Additionally, gures for

2020 and 2021 should be approached with caution due to potential disruptions created by COVID-19.

Despite these constraints, signicant eorts were made to consult the most relevant stakeholders and to include a large

representative sample of Member States.

11

2. The construction sector: Key characteristics and

challenges

Main ndings

• The construction sector is essential for the EU economy, adding signicant value and employing

around 13million people. The average growth rate of employment in 2021 was around 3%. The

gross value added (GVA) share of the sector in the EU was around 5.5% in 2021.

• The construction sector is characterised by the signicant presence of posted workers and by

distinct mobility patterns across Member States. Based on available data on PDs A1 issued in

2021, around one out of four PDs A1 issued (under Article 12) in the EU are granted for services

in the construction sector, with a signicant dierence observed between western and southern

(15%) and central and eastern Member States (49%). Germany is both a main receiving and

sending country for posted workers in the construction sector, whereas Poland is the primary

sending country–the corridor from Poland to Germany is the primary corridor in the EU. Posted

construction workers also play an important role in Belgium from a receiving perspective and

in Slovenia from a sending perspective. Figures from 2021 also indicate a recovery from the

COVID-19 pandemic in most of the Member States that have national-level data available.

• Subcontracting is a prevalent practice in the construction sector in the EU, enabling access to

cheap labour and specialised skills and oering a way to manage market uctuations and labour

shortages. Subcontracting chains in this sector can become complex, especially when they involve

multiple companies from dierent Member States, creating diculties for labour enforcement

authorities and trade unions to identify the ‘actual employer’ and protect workers’ rights.

• Temporary work agencies play a pivotal role in subcontracting chains by providing workers

for dierent stages of construction projects, including both unskilled and highly specialised

workers. National labour inspectorates face diculties in monitoring and inspecting these

agencies, often due to their use of virtual oces or letterbox companies to evade inspections.

Ensuring compliance and preventing abuses in the construction sector requires regular

inspections, improved information sharing between labour authorities, and access to national

databases on posted workers, tax and social security.

• The construction sector is one of the main sectors employing posted third country nationals

(TCNs), together with (road freight) transport and agriculture. There are, however, notable

dierences between Member States. For instance, Malta and Romania have low numbers of

posted TCNs in the construction sector; in contrast, incoming TCNs represent a signicant share

of posted workers in Belgium and Austria. Posted TCN workers are more vulnerable than EU

posted workers due, inter alia, to their dependency on their employer for the renewal of the

work and residence permits, language barriers, more exposure to irregular employment, and

subsequent non-payment of social contributions and health insurance. Such vulnerability is

most likely to be enhanced in the construction sector considering, inter alia, the occupational

health and safety risks inherent to this sector.

• The setting up of letterbox companies, the non-respect of working conditions, bogus self-

employment, fraudulent PD A1 forms and illegal employment of TCNs or their fraudulent

posting represent the most signicant and recurrent violations and abusive practices.

Providing an introductory overview of the construction sector labour market in the EU, this section will rst detail the

relevance of the construction sector in the EU economy (Section2.1). It will then describe the key characteristics of the EU

construction sector relevant to this study, focusing in particular on the use of subcontracting practices and temporary work

12

agencies (Section2.2), the number of posted workers in the construction sector and key mobility patterns (Section2.3),

the role of posted TCN workers (Section2.4) and the abusive practices related to postings in the construction sector

(Section2.5).

2.1 The construction sector in the EU economy

With more than 3million enterprises, the EU construction sector has an annual turnover of more than EUR1500billion. One

way to assess its size is by looking at the GVA, which is a measure of the sector’s contribution to the overall economy(

4

).

According to the latest available Eurostat data, the GVA share of the construction industry was around 5–6% between 2010

and 2021. This gure reached its peak of 5.8% in 2010, but fell to 5.1% during 2014–2017, before increasing again to 5.5%

between 2020 and 2021(

5

). During this period, several Member States experienced a decrease in the GVA share from the

construction sector, with the main reductions being in Bulgaria, Greece, Spain and Slovakia. In contrast, Denmark, Germany,

Lithuania, Hungary and Finland experienced the highest growth. In 2021, the GVA share was particularly high in Lithuania,

Austria, Romania and Finland, in all of them contributing to 7% or more of the total GVA(

6

).

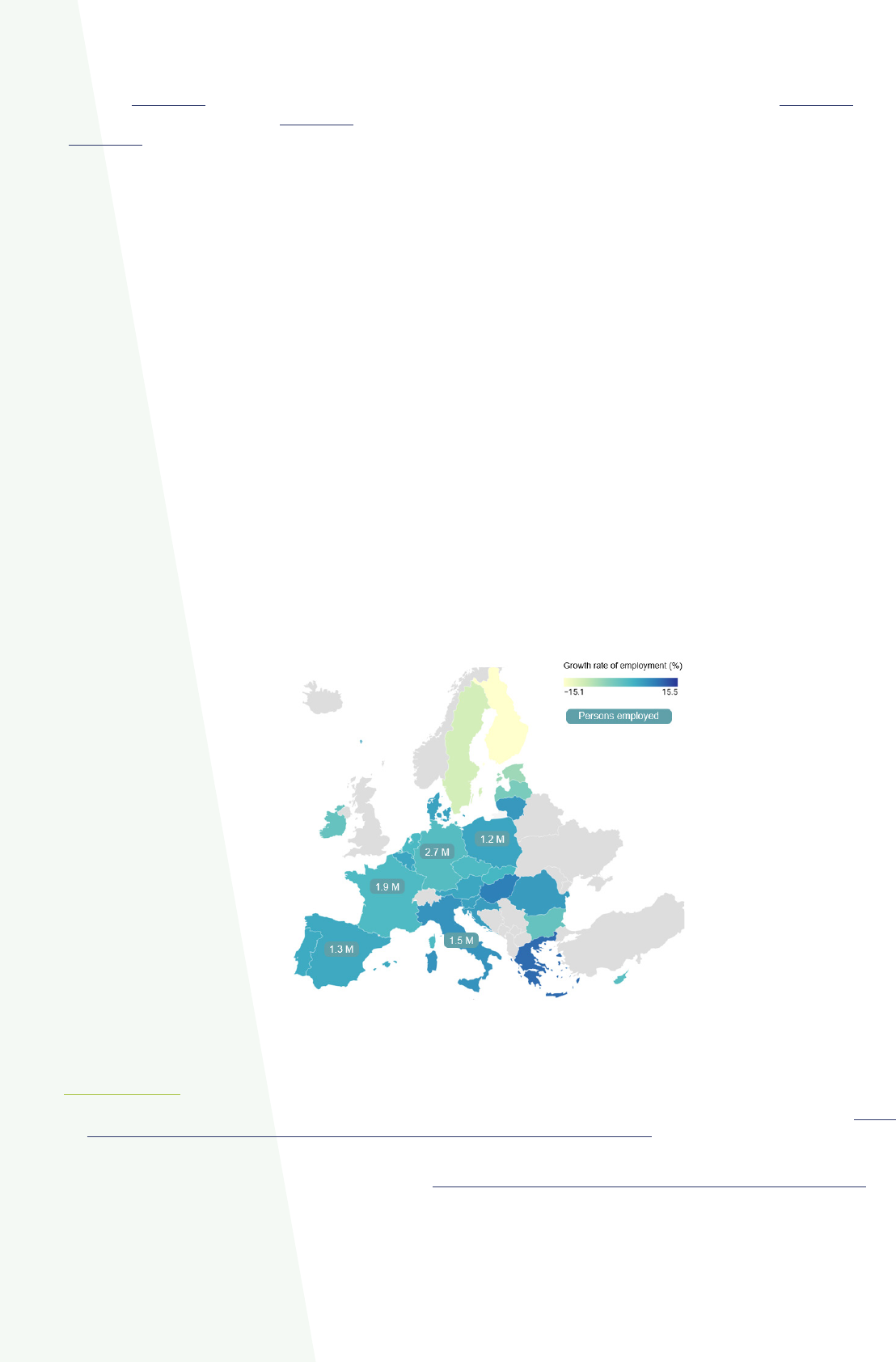

In addition to GVA, employment gures can also provide insights into the size of the sector. Overall, the EU construction

sector directly employs around 13million people(

7

) and had an average employment growth rate of employment (between

2020 and 2021) of around 3%(

8

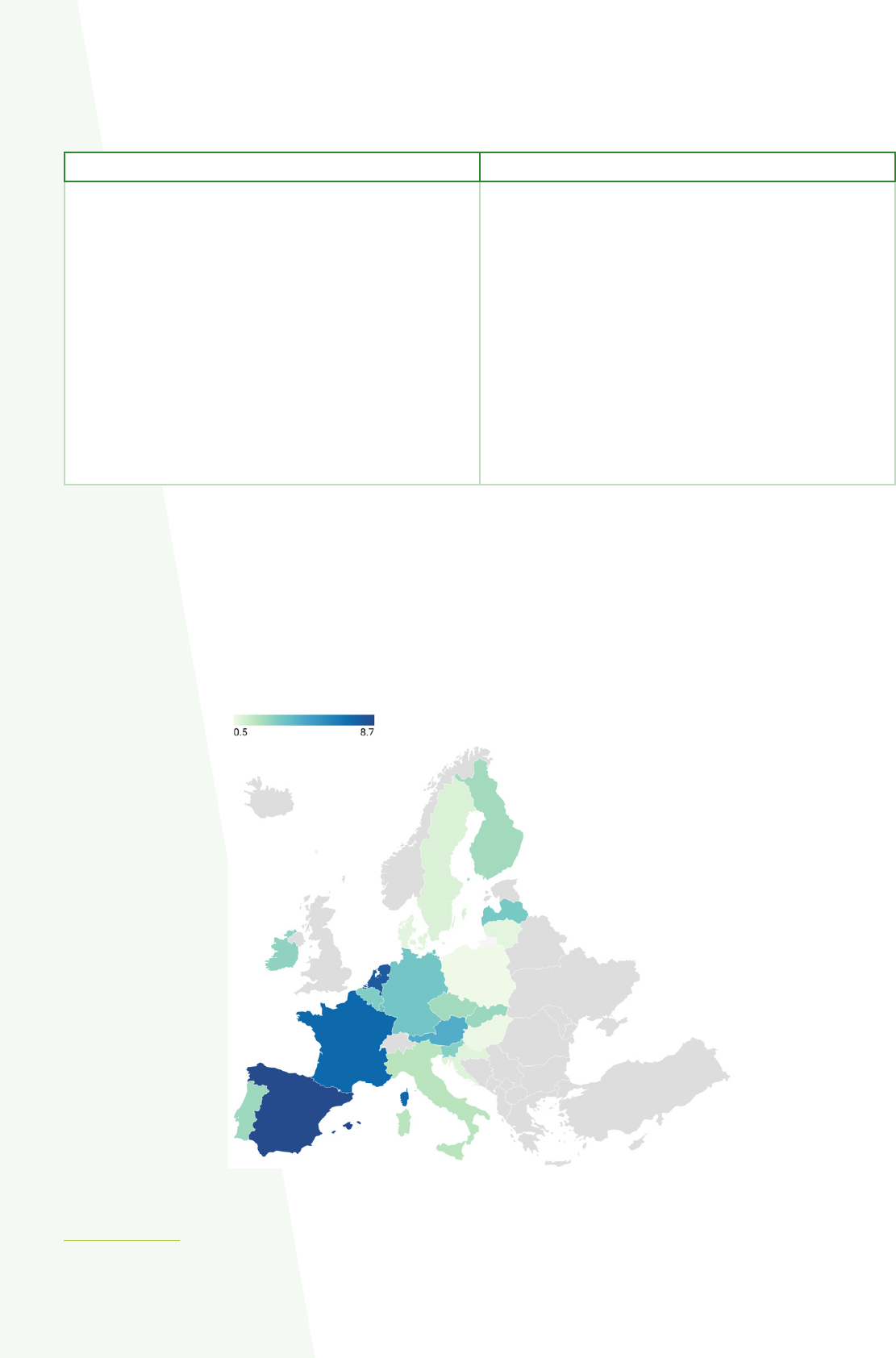

). The map in Figure1 shows these gures by Member State. Germany had the highest

number of workers employed in the construction sector in 2021, followed by France, Italy, Spain and Poland. Relative to the

total workforce, Luxembourg has the highest share of workers in construction (around 17%), followed by Lithuania (9.5%),

Cyprus (9%) and Austria (8.5%)(

9

). When it comes to employment growth rates between 2020 and 2021, Greece, Hungary

and Italy had the highest gures. In Scandinavian and Baltic states, the growth rates have been decreasing and, considering

the high GVA, a lower level of employment may indicate an increase in productivity, further conrmed by the high extent of

digitalisation adopted in the construction sector within these countries(

10

).

Figure1: Number of employed and growth rate of employment (in%) in the construction

sector, 2021

NB:Figures for total persons employed are shown only for countries with numbers above 1million. Growth rate of employment (in%) is relative to the

previous year.

Source: Eurostat, enterprise statistics, SBS_SC_OVW

(

4

) Eurostat defines GVA as ‘output (at basic prices) minus intermediate consumption (at purchaser prices)’. Eurostat, ‘Statistics Explained’ (https://

ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Gross_value_added&lang=en).

(

5

) Data for 2020 and 2021 may be subject to limitations and distortions due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Figures for these years

should be interpreted with caution.

(

6

) Eurostat, annual national accounts, NAMA_10_A10. See also: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/digpub/housing/bloc-3a.html?lang=en.

(

7

) Eurostat, labour force survey data, LFSA_EGAN2, and Eurostat, structural business statistics– industry and construction, SBS_NA_CON_R2.

(

8

) Eurostat, enterprise statistics, SBS_SC_OVW. Data for 2020 and 2021 may be subject to limitations and distortions due to the impact of the

COVID-19 pandemic. Figures for these years should be interpreted with caution.

(

9

) Eurostat, enterprise statistics, SBS_SC_OVW; Eurostat, labour force survey, LFSA_EGAN22D.

(

10

) European Construction Sector Observatory (ECSO), Digitalisation in the construction sector: Analytical report, European Commission, 2021.

13

In the EU, most of the construction industry (99%) is composed of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), namely

enterprises with fewer than 250 employees(

11

). Among those, micro-enterprises (with fewer than 10 workers) represent the

largest share in the EU, accounting for around 94% of the construction sector(

12

).

2.2 Subcontracting and the role of temporary work agencies

As further detailed in Section4(2), subcontracting is a prevalent practice in the construction sector in the EU, enabling

access to cheap labour and specialised skills and oering a way to manage market uctuations and labour shortages.

A subcontracting chain forms when a large contractor, hired by an investor or the investor itself, engages one or more

subcontractors who bring their own personnel or engage another legal entity, such as a temporary employment agency(

13

).

These chains can become complex, especially when they involve multiple companies from dierent Member States,

increasing uncertainty around employment arrangements. This complexity can result in an erosion of workers’ rights, and it

is particularly challenging at the lower levels of the chain for labour enforcement authorities and trade unions to identify the

‘actual employer’ and protect workers’ rights.

The growth of labour market intermediaries in the form of temporary work agencies has created additional complexity

in the subcontracting chain. Temporary work agencies play a pivotal role in subcontracting chains by providing workers

for the dierent stages of construction projects. This can include both unskilled labour and highly specialised workers

such as architects and engineers. In doing so, they can help promote labour mobility within the EU by making it easier for

companies to hire temporary workers from other Member States. Within the EU legal framework, temporary work agencies

are regulated by the Directive on Temporary Agency Work (Directive 2008/104/EC)(

14

), which ensures the protection of

temporary agency workers and the principle of equal treatment(

15

). The directive does not set standards on pay, working

conditions or occupational health and safety for temporary agency workers, but requires that temporary agency workers

are entitled to the same rights as directly hired workers in areas such as the duration of working time, overtime, breaks, rest

periods, night work, holidays and public holidays and pay(

16

). The revision of the Posting of Workers Directive(

17

) ensures

equal treatment of posted temporary workers. The same conditions applicable to national temporary work agencies will

also apply to cross-border agencies hiring workers.

Article 3 of the directive denes temporary work agencies as ‘any natural or legal person who, in compliance with national

law, concludes contracts of employment or employment relationships with temporary agency workers in order to assign

them to user undertakings to work there temporarily under their supervision and direction’. The relationships between the

temporary work agency (supplier/lender of workers’ services), the temporary agency worker and the contracting business

(user/borrower of workers’ services) are established via two contracts: one between the agency and the worker, and a

second between the agency and the business. Therefore, the worker is a formal employee of the temporary work agency

and there is no contract between the contracting business and the worker(

18

). Even though the specic responsibilities

of the temporary work agency and contracting business may vary depending on the national regulations and collective

agreements, the table below provides a general outline of their distribution between the two parties.

(

11

)

Eurostat, enterprise statistics, SBS_SC_OVW.

(

12

)

Ibid.

(

13

) European Parliament, Directorate-General for Parliamentary Research Services, Heinen,A., Kessler,B., and Müller,A., Liability in subcontracting

chains: national rules and the need for a European framework, European Parliament, 2017.

(

14

) Directive 2008/104/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19November 2008 on temporary agency work (OJ L327, 5.12.2008,

p.9).

(

15

) Article 2 of Directive 2008/104/EC.

(

16

) Further instruments shaping the legal framework for temporary work agencies are the International Labour Organisation (ILO) Convention

No181 and the European Social Charter. The former provides guidelines for the operation of private employment agencies (an umbrella group

that includes temporary work agencies) and emphasises the importance of protecting the rights of workers who are placed through such

agencies. Although no explicit reference to temporary work agencies is made in the provisions of the 1961 and 1996 ESC, the charter requires

Member States to ensure that the social and economic rights are applied to all workers, regardless of the nature of their contracts. See:

Countouris,N., Deakin,S., Freedland,M., Koukiadaki,A., and Prassl,J., Report on temporary employment agencies and temporary agency work,

ILO, 2016, pp.29–35.

(

17

) Directive 96/71/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16December 1996 concerning the posting of workers in the framework of

the provision of services (OJ L18, 21.1.1997, p.1)

(

18

) Kessler,B., et al., 2017.

14

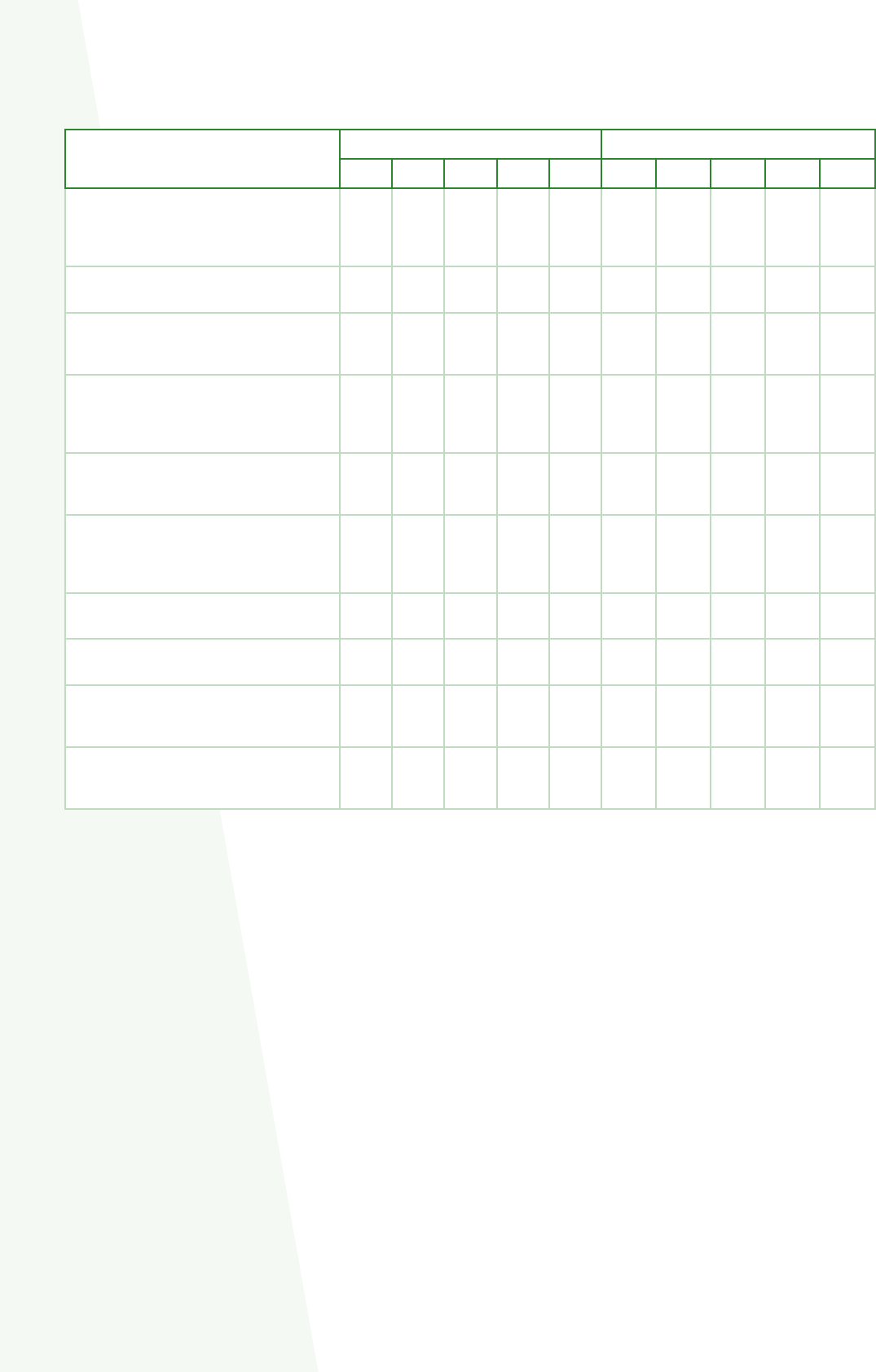

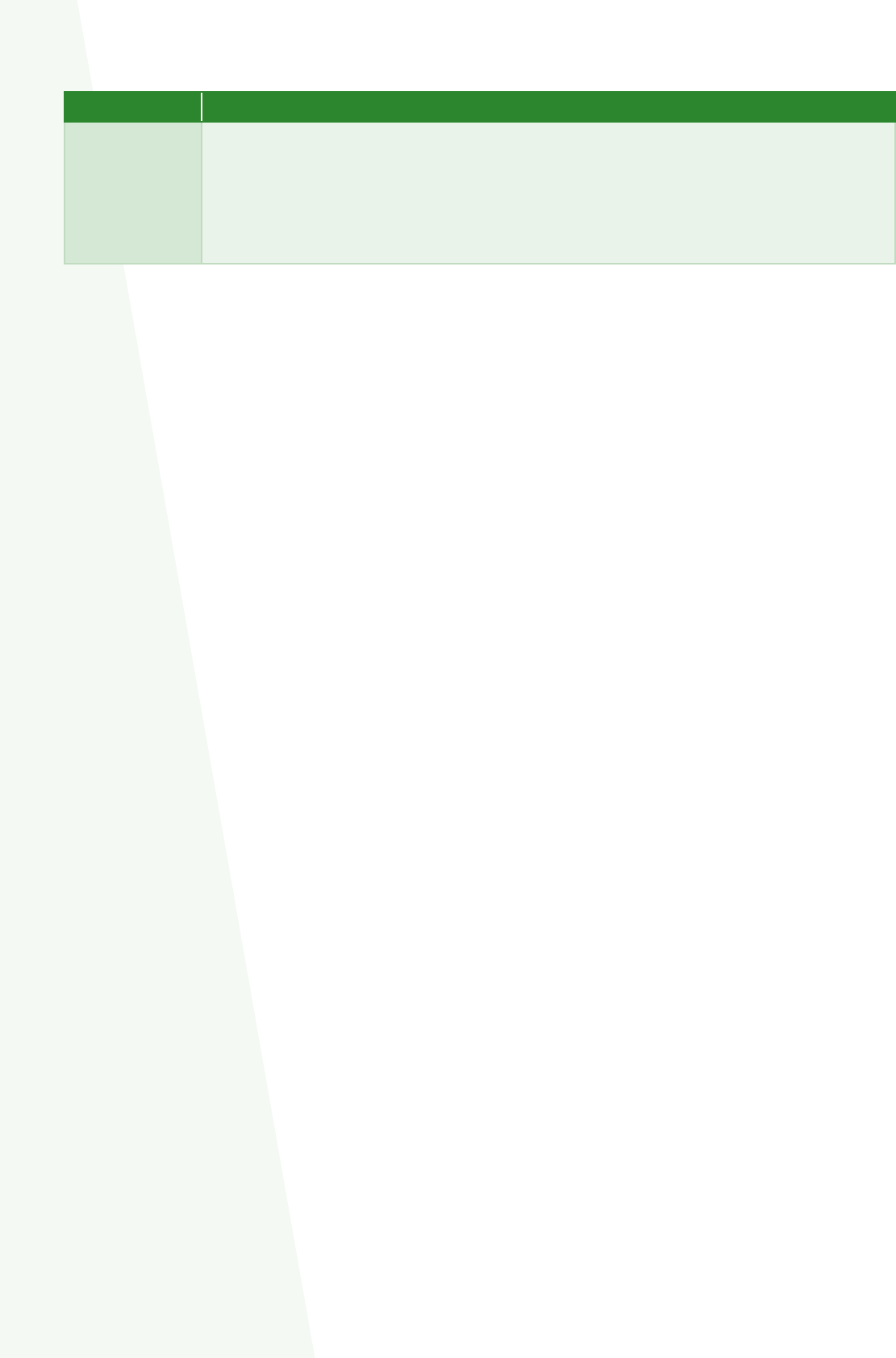

Table2: Roles and responsibilities of the contracting business and temporary work

agency

Contracting business Temporary work agency

Providing a safe working environment for temporary agency

workers, including any necessary safety equipment or training.

They must also comply with the legal framework relevant to

occupational health and safety.

Providing temporary agency workers with access to the same

collective facilities and amenities as permanent workers, such

as sta canteens, childcare facilities and transport services.

Ensuring equal treatment of temporary agency workers so that

they receive the same basic working and employment conditions

as if they had been recruited directly by the user company,

including pay, working hours, and any other relevant terms and

conditions. They must not discriminate against temporary agency

workers on the grounds of their employment status or any other

characteristic.

Supervising and managing temporary agency workers. They

must ensure that the workers receive adequate training and

support to perform their job, and that they are treated fairly and

respectfully.

Recruiting and selecting temporary agency workers for user

companies, and ensuring that the workers have the necessary

skills and qualications for performing the job and all the

necessary documentation and permits (including PD A1 in the

case of posted workers) for working in the relevant country.

Entering into contracts with temporary agency workers.

These contracts should specify the terms and conditions of

employment, including the duration of the assignment, the rate

of pay, working hours and any other relevant details.

Providing information to temporary agency workers about their

employment conditions, including their pay, working hours and

any other relevant terms and conditions.

Paying temporary agency workers, including any overtime

or additional compensation required by law. They must also

deduct and remit any taxes, social security contributions or other

mandatory deductions required by law.

Source: Author’s elaboration, based on Kessler,B., et al., 2017; and Countouris,N., Deakin,S., Freedland,M., Koukiadaki,A., and Prassl,J., Report on temporary

employment agencies and temporary agency work, ILO, 2016, p.35.

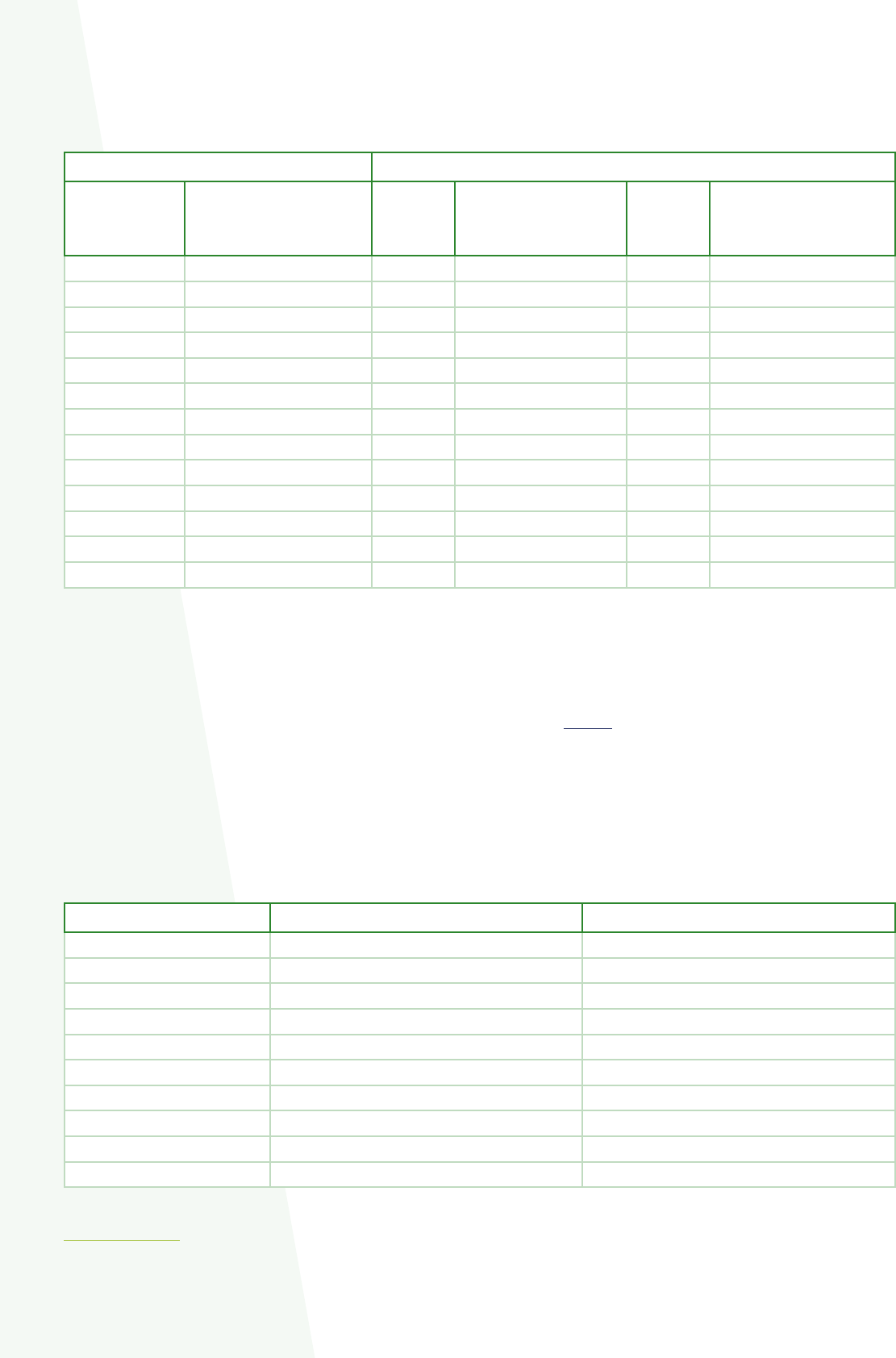

According to Eurostat data, in 2021, 3.4% of employees in the EU construction sector worked for a temporary work agency.

This gure is one percentage point higher than for the rest of the economy and has stayed relatively stable over that last

6years (3.1% in 2015)(

19

). The map below provides a breakdown by Member State. Spain, the Netherlands, and France

report the highest shares of workers employed by temporary work agencies: around 9%, 8% and 7%, respectively.

Figure2: Temporary work agency workers in the construction sector (% of total

employees), 2021

NB:No data for Bulgaria, Estonia, Cyprus, Malta and Romania. Greece excluded due to a break in time series. Figures are in percentage of total employees

between 20–64years old.

Source: Eurostat, LFS, LFSA_QOE_4A6R2.

(

19

) Eurostat, Labour Force Survey (LFS), LFSA_QOE_4A6R2.

15

Temporary work agencies, although very exible and cost-eective, may be subject to fraudulent use(

20

). As temporary

work agencies are not directly linked with the activities of construction businesses, they may take advantage of the complex

employment relationships and context in which they operate to avoid legal wage payments, and bypass vocational

education and training and occupational safety and health (OSH) requirements. Certain studies further suggest that

fraudulent agencies have created business models that generate income from charging high recruitment fees(

21

), oering

exploitative arrangements when it comes to the posting of workers, or disguising employment as business trips(

22

). Some

of the temporary work agencies may be unregistered, unlicensed or underreporting the economic activities undertaken

and can force EU mobile workers into undeclared work(

23

). In general, all Member States have in place a clear statutory

framework that regulates and limits the terms of use of temporary work agencies to prevent fraudulent practices(

24

). In

Germany, for instance, temporary work agencies are strictly forbidden in the construction sector(

25

).

In Poland, an issue persists regarding temporary work agencies. According to the Polish Ministry of Family and Social Policy,

approximately 9000 temporary work agencies are registered in the country, yet they exhibit a high annual turnover rate–

with over 20% disappearing each year– which signals potential fraudulent activities within these companies. To address

this problem, the Polish Labour Inspectorate suggests regular inspections of cross-border postings from these temporary

work agencies. Such measures are crucial in preventing abuses, particularly in the construction sector, and ensuring

compliance inter alia with OSH requirements.

Diculties in monitoring and inspecting temporary work agencies were reported by several national labour inspectorates,

as those agencies often set up ‘virtual oces’ or letterbox companies to evade inspections and legal consequences for

non-compliance(

26

). Often, there is also a lack of tools to monitor the labour relations of workers who are posted to other

Member States. Addressing these issues may include prompt and ecient access by national authorities to information

from other Member States’ national databases regarding posted workers, tax and social security, and also an increased

accessibility of information ow between labour authorities and workers(

27

).

2.3 Posted workers and key mobility patterns

This section examines the number and share of posted workers in the construction sector and their key mobility patterns.

This is based on data from the portable documents A1 (PDs A1)(

28

) and on data obtained from prior declaration tools (PDTs)

and other micro-data sources.

Based on available data on postings in 2021, around one in four PDs A1 issued were granted for services in the EU

construction sector. The estimated total number of PDs A1 issued in the EU construction sector was approximately 833650.

Germany was the primary receiving country for posted workers in the EU construction sector, while Poland was the main

sending country. These Member States also made up the primary corridor in the EU, namely from Poland to Germany. At the

same time, posted construction workers played an important role in Belgium from a receiving perspective and in Slovenia

from a sending perspective. Moreover, gures from 2021 indicated a recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic in most

Member States when national-level data were available.

As for posted workers in general, it is important to rst highlight the challenges and gaps in terms of data collection

regarding posted workers in the construction sector(

29

). The availability of data on intra-EU posting depends mainly on

the extent to which companies eectively declare their posting activities in both the sending and receiving Member State,

alongside the reporting mechanisms in place. Nevertheless, there is a lack of uniformity in data collection approaches

(

20

) Pavlovaite,I., ‘Tools and approaches to tackle fraudulent temporary agency work, prompting undeclared work’, European Platform Tackling

Undeclared Work, 2020; Pavlovaite,I., ‘Tools and approaches to tackle fraudulent temporary agency work, prompting undeclared work’,

European Platform Tackling Undeclared Work, 2021; Stefanov,R., et al., 2021.

(

21

) Although Directive 2008/104/EC and ILO Convention No181 prohibit temporary work agencies from charging any fees for recruitment,

placement or providing information about job vacancies, there may be certain exceptions to this rule in some Member States (e.g. fees

related to the processing of work permits or visas). This also depends on the transposition of the directive provisions in Member States. See:

Schömann,I., and Guedes,C., Temporary Agency Work in the European Union: Implementation of Directive 2008/104/EC in EU Member States,

European Trade Union Institute (ETUI), 2012.

(

22

) Pavlovaite,I., 2020, p.5.

(

23

) Stefanov,R. et al., 2021.

(

24

) Kessler,B., et al., 2017, p.20.

(

25

) Temporary Employment Act (LS 1972– Ger. F.R. 2), Section1. More information can also be found here: https://www.zoll.de/EN/Businesses/

Work/Foreign-domiciled-employers-posting/Temporary-work-temporary-worker-assignment/Requirements/requirements_node.html.

(

26

) Stefanov,R., et al., 2021.

(

27

) Ibid.

(

28

) The PD A1 is a document that must be requested by the posting undertaking or the self-employed person to prove that a worker or a self-

employed person remains subject to the social security system of the sending Member State.

(

29

) De Wispelaere,F., De Smedt,L., and Pacolet,J. Posted workers in the European Union: Facts and figures. Leuven: POSTING.STAT project

VS/2020/0499, 2022b, pp.17–19.

16

among Member States (including dierences in information requested, type of procedure, etc.). In practice, authorities in

both countries may not always be informed about posting activities, partially due to notable dierences in terms of the use,

methodology and scope of declaration tools and prior declaration forms. The available posting data from both PDs A1 and

PDTs might therefore not always reect reality(

30

). Some countries have recently taken measures to increase compliance

by imposing stricter conditions on the PD A1 requirements for being legally posted. France and Austria, for example, have

implemented penalties or sanctions for companies that are not able to present a valid PD A1, and authorities are conducting

more frequent and thorough checks on whether posted workers possess the necessary PD A1(

31

).

Despite these limitations, PD A1 statistics remain the most useful source for comparing Member States at the EU level and

provide a good estimation of postings/ posted workers in the construction sector. At the national level, PDTs and other

micro-data can help complement the information, lling in some gaps and revealing potential trends within Member States.

2.3.1 Data from portable documents A1

At the EU level, data from 2021 are used and focus specically on PDs A1. The available statistics distinguish between PDs

A1 issued under Article 12 (i.e. employees/ the self-employed who normally carry out activities in one Member State and are

posted to another) and Article 13 (i.e. employees/ the self-employed engaged in activities in two or more Member States)

of the Basic Regulation(

32

). As such, the dierent types of PDs A1 data collected provide valuable insights into the mobility

patterns of posted workers within the EU.

It is important to note that several Member States– including signicant net receiving and sending countries– lack available

data on PDs A1 issued from a sending perspective under Article 12 in the sector in 2021. These are Bulgaria, Denmark,

Ireland, Greece, Spain, Italy, Hungary and the Netherlands(

33

). Additionally, under Article 13, information on PDs A1 is

unavailable for the countries mentioned above as well as for Czechia, Germany, Portugal and Romania. This data gap partly

stems from the absence of information about the location of cross-border activities for these individuals, resulting in data

regarding the receiving Member States being unobtainable, and also from countries not fully sharing the requested data.

The main Member States receiving and sending construction services in 2021, based on the total number of PDs A1 issued

under Article 12 of the Basic Regulation(

34

), are shown in Table3. While Germany was the main receiving country in terms

of absolute numbers, Poland was the main sending EU Member State. In order to indicate the signicance of postings in the

workforce of each Member State’s construction sector, the table also shows an estimation of the PDs A1 issued as a share of

all workers in the sector. Notably, Slovenia and Slovakia stand out with remarkably high proportions of outgoing postings at

52% and 28% respectively. This may suggest a widespread use of and reliance on a possible ‘business model’ by employers

in these countries’ construction sectors whereby workers do not get employed in the country but are immediately posted

to another Member State(

35

). At the same time, the share for Belgium (17%) indicates a high level of posted workers in its

construction sector from a receiving perspective.

(

30

) The reported figures only indicate the intention to provide services in the Member State, without confirming the actual provision of these

services. There are also differences in the definition of ‘posted’ between the Basic Regulation and the Posting of Workers Directive, which may

result in workers (not) being counted in the PDs A1 statistics. Moreover, while undertakings are required to inform competent institutions

before a posting, this may not always happen, resulting in further discrepancies between the number of PDs A1 issued, postings of which

Member States have been notified and the actual number of persons being sent abroad as posted workers. These tools may therefore over- or

underestimate the actual number of posted workers, making it challenging to directly compare or extrapolate the data.

(

31

) De Wispelaere,F., De Smedt,L., and Pacolet,J., Posted Workers in the European Union: Facts and figures. Leuven: POSTING.STAT project

VS/2020/0499, 2022b, pp.16–19.

(

32

) Regulation (EC) No 883/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29April 2004 on the coordination of social security systems (OJ

L166, 30.4.2004, p.1).

(

33

) In 2020, Hungary and the Netherlands did have data available in this context.

(

34

) De Wispelaere,F., De Smedt,L. and Pacolet,J., Posting of Workers: Report on A1 Portable Documents issued in 2021, HIVA-KU Leuven, 2023,

pp.55–56.

(

35

) De Wispelaere,F., De Smedt,L. and Pacolet,J., Posted workers in the European Union: Facts and figures. Leuven: POSTING.STAT project

VS/2020/0499, 2022b, p.36.

17

Table3: Main receiving/sending Member States of postings in the construction sector,

based on PDs A1 issued under Article 12, 2021

Receiving Member State Sending Member State

Member State

No. of PDs

A1 issued

under

Article 12

Estimated postings

as% of total

employment in the

construction sector

Member State

No. of PDs

A1 issued

under

Article 12

Estimated postings

as% of total

employment in the

construction sector

DE 151146 5% PL 104308 10%

BE 54852 17% DE 64813 2%

FR 47125 3% SI 41785 52%

AT 36923 10% SK 41209 28%

NL 24549 4% PT 34635 9%

NB:Data unavailable for Bulgaria , Denmark, Ireland, Greece, Spain, Italy and Hungary.

Source: De Wispelaere et al., 2023; ECSO 2021 employment data (number of persons employed in construction); author’s calculations.

From a sending perspective, in the EU in 2021, 25.9% of all PDs A1 issued under Article 12 were granted for services in the

construction sector(

36

). This has increased from 23.9% in the previous year. Excluding Germany, this share signicantly rises

to 42.8%, highlighting the greater number of posted workers in construction for the rest of the sending Member States.

Moreover, there is a notable dierence between mostly western and southern Member States (15%)(

37

) and mostly central

and eastern European Member States (48.9%)(

38

). This indicates that the posting of workers in the construction sector has a

stronger geographical dimension compared to the more evenly distributed phenomenon of posting across various sectors

of Member States. Under Article 13, 19.3% of PDs A1 issued were applicable to the construction sector(

39

) (compared to

18.3% in 2020).

Using these average shares and the total number of PDs A1 issued in each Member State, an estimation can be made of the

total number of PDs A1 issued in the EU construction sector (under both Articles 12 and 13). As mentioned earlier, from a

sending perspective, there are missing gures for eight Member States regarding PDs A1 issued under Article 12, and for 12

Member States for those issued under Article 13. After making a number of inevitable assumptions due mainly to missing

data(

40

), the estimated total number of PDs A1 issued in the EU construction sector in 2021 is approximately 833650,

comprised of 590728 PDs A1 under Article 12 and 242922 PDs A1 under Article 13. Nonetheless, it is important to note that,

rather than exact numbers, these gures represent estimates relying on several assumptions.

Table4 provides information on the Member States where the construction sector has the highest share across all sectors

for incoming and outgoing posted workers in 2021. The table is based on PDs A1 issued under Article 12 for incoming

posted workers and PDs A1 issued under both Articles 12 and 13 for outgoing posted workers in the construction sector,

expressed as a share of the total incoming/outgoing postings(

41

). The data suggest again that western Member States were

mainly represented among incoming posted workers, whereas central and eastern Member States were mostly observed

as having outgoing postings. More than one out of four incoming posted workers were active in the construction sector

in Belgium, Germany, France, Croatia, Luxembourg, Finland and Sweden. From a sending perspective, Estonia is the only

Member State with available data that shows the construction sector as the largest among those posted under Article 13.

(

36

) De Wispelaere,F., De Smedt,L. and Pacolet,J., Posting of Workers: Report on A1 Portable Documents issued in 2021, HIVA-KU Leuven, 2023,

p.33. This figure excludes Bulgaria, Denmark, Ireland, Greece, Spain, Italy and Hungary, and includes European Free Trade Association (EFTA)

member states Iceland and Liechtenstein.

(

37

) Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, Finland and Sweden.

(

38

) Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia and Slovakia.

(

39

) De Wispelaere,F., De Smedt,L., and Pacolet,J., Posting of Workers: Report on A1 Portable Documents issued in 2021, HIVA-KU Leuven, 2023, p.42.

This figure excludes Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Greece, Spain, Italy, Hungary, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Romania, and

includes the EFTA member state Liechtenstein.

(

40

) For Article 12, the missing values are calculated by assigning the missing Member States the average construction shares of western and

southern (i.e. Denmark, Ireland, Greece) and central and eastern (i.e. Bulgaria) Member States, which are 15% and 48.9% respectively.

However, in the cases of Spain and Italy, it is assumed that they are main sending countries, and therefore the share of 48.9% is used. For

Hungary and the Netherlands, the average construction shares in 2020 are taken, which were 44.2% and 13.8% respectively. For Article 13,

the average EU construction share (19.3%) is used for all missing Member States.

(

41

) De Wispelaere,F., De Smedt,L., and Pacolet,J., Posting of Workers: Report on A1 Portable Documents issued in 2021, HIVA-KU Leuven, 2023,

pp.33–34 and 42.

18

Table4: Member States where construction is the primary sector for incoming/outgoing

posted workers, 2021

Incoming posted workers Outgoing posted workers

Member State

Construction as% of total

PDs A1 issued under Art.

12

Member

State

Construction as% of

total PDs A1 issued

under Art. 12

Member

State

Construction as% of total

PDs A1 issued under Art.

13

DE 55.1% PT 60.3% EE 54.4%

HR 44.2% RO 53.9%

SE 44.1% EE 53.6%

LU 38.7% SK 52.5%

BE 38.6% PL 46.7%

FI 29.1% HR 45.8%

FR 25.6% HU 44.2%

AT 22.2% CZ 43.4%

SI 21.4% LU 42.7%

SI 41.4%

LV 41.2%

LT 39.7%

AT 28.5%

NB:Only the Member States that reported construction as the sector with the largest share among all sectors are included in the table. 2020 gures were

used for HU and NL. Data unavailable under Art. 12 for BG, DK, EL, ES, IE, and IT. Data unavailable under Art. 13 for BG, CZ, DE, DK, EL, ES, HU, IE, IT, NL, PT,

and RO.

Source: De Wispelaere et al., (2023)

The primary corridor of postings in the construction sector in 2021, similar to 2020, was from Poland to Germany, with

a total of 53914 PDs A1 issued by Poland under Article 12(

42

). This represents a 17% increase compared to 2020, which

was a recovery from the 11% decrease following the COVID-19 pandemic. Table5 presents the other main ows between

Member States in the construction sector. Following the Poland–Germany corridor, signicant ows included Slovakia–

Germany (23148 PDs A1) and Slovenia–Germany (22374 PDs A1). Belgium and France mainly hosted posted construction

workers from Portugal and Poland, whereas Austria primarily received workers from Germany and Slovenia. Nonetheless, it

is important to note that data for several major sending Member States, including Italy and Spain, were unavailable.

Table5: Main corridors of postings in the construction sector between Member States,

2021

Sending Member State Receiving Member State Number of PDs A1

PL DE 53914

SK DE 23148

SI DE 22374

DE AT 17097

PT FR 12383

PL FR 12358

PL SE 11011

PT BE 10886

PL BE 9501

SI AT 9193

NB:Data unavailable for BG, DK, EL, ES, HU, IE, and IT.

Source: De Wispelaere et al., (2023)

(

42

) Ibid, p.32.

19

When looking at the division of both types of PD A1 granted to individuals employed in the construction sector in the EU,

74% were issued under Article 12, while 26% were issued under Article 13 in 2021. This represents a wider gap compared

to previous years, when the percentages had been converging every year between 2017–2020 to reach 65% and 35%

respectively in 2020. This shift may suggest an increase in the signicance of Article 12 across the EU as a consequence of

the COVID-19 pandemic, but these gures should be treated as tentative(

43

). Only six Member States reported more PDs A1

issued in construction under Article 13 compared to Article 12: Cyprus (97%), Latvia (75%), Estonia (72%), Sweden (70%),

Finland (53%) and Lithuania (51%)(

44

).

2.3.2 Data from prior declaration tools and micro-data

The other sources of data to be examined, collected mainly from PDTs, are at the national level. The national declaration

systems, implemented by all 27 Member States, assist competent authorities in identifying posted workers and complement

the information provided by PDs A1. Other micro-data sources can assist with complementing and conrming previously

made reections. There are signicant dierences found between Member States in terms of the implementation,

procedures, and requirements of their respective tools(

45

).

This section focuses on a selection of net receiving countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, and the

Netherlands) and net sending countries (Italy, Poland, Slovenia, and Spain). To the extent that data are available, these

Member States are presented from both the receiving and sending perspective (in alphabetical order). The primary source is

the POSTING.STAT study conducted by HIVA-KU Leuven. Some key sending countries (e.g. Portugal, Slovakia, Romania) were

not included in the study due to a lack of data.

Table6 summarises the data for the Member States that are covered in the rest of the section regarding posted workers as a

share of total employment in the construction sector. In comparison to the PDs A1 data presented in Table 3, the PDT data

and micro-data suggest a signicantly dierent share of posted workers on the workforce in construction. While both types

of data are valuable as proxies for evaluating the scope of postings and ows of posted, an advantage of PDT data is that, as

opposed to PDs A1, for the sector of construction, national PDTs normally require a separate declaration for every envisaged

posting. Belgium appears to rely signicantly on incoming posted workers in the construction sector, whereas gures from

Slovenia suggest again a high share of outgoing posted workers relative to the workforce.

Table6: Posted workers in the construction sector as a share of total employment

according to Art. 12 PDs A1 data, 2021

Receiving Member State Sending Member State

Member State

Estimated posted workers as% of total

employment in the construction sector

Member State

Estimated posted workers as% of total

employment in the construction sector

BE 26% SI 27%

DE 10% PL 26%

NL 7% ES 4%

AT 5%

FR 5%

LU 1%

NB:2019 gures for AT and FR. 2020 gures for DE, ES, LU, PL, and SI. 2021 gures for BE and NL.

Source: POSTING.STAT project; ECSO (2021) employment data (Number of persons empIoyed in construction); author’s calculations.

Furthermore, the data conrm that construction was a signicant sector for posted workers, accounting for a large share of

all posted workers across Member States. As observed from the PD A1 data, the PDT data show that Germany was the main

receiving country, while Poland was the primary sending country. When gures from 2021 are available, Member States

(

43

) Drawing definitive conclusions is not feasible as these shares are based on a short time frame and (somewhat) different sets of countries each

year. For 2021, coverage was limited to 15 EU Member States (Belgium, Estonia, France, Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta,

Austria, Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland and Sweden) and one EFTA member state (Liechtenstein).

(

44

) De Wispelaere,F., De Smedt,L., and Pacolet,J., Posting of Workers: Report on A1 Portable Documents issued in 2021, HIVA-KU Leuven, 2023,

pp.42–43.

(

45

) De Wispelaere,F., De Smedt,L., and Pacolet,J., Posting of Workers: Collection of data from the prior declaration tools– Reference year 2020, HIVA-

KU Leuven, 2022a, pp.11–17.

20

often report a recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic compared to 2020 gures. There was also a regional dimension at

play, as posting activities appeared to hold particular importance between neighbouring countries (e.g. Poland–Germany

and Spain–France). In addition, TCNs, such as Ukrainians and Bosnians, played a vital role in the labour force of the

construction sector in the EU, and their presence among posted workers was increasingly prominent.

2.3.2.1 Austria

The Austrian construction sector was a signicant receiver as well as sender of posted workers. According to the Zentrale

Koordinationsstelle des Bundesministeriums für Finanzen forms from the Austrian Financial Police, 83634 postings were

recorded in 2019 by prior declarations in the construction sector (8% of all postings), whereas there were 20717 individual

posted workers (3% of all individual posted workers)(

46

). The number of posted workers was estimated at 16561, which was

around 5% of the total 309440 people employed in the Austrian construction sector(

47

). The share of EU citizens (including

Austrians) in the construction sector in Austria was 88% and the share of TCNs was 12%(

48

).

In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, postings in the construction sector recovered quickly as construction sites

remained open during the lockdowns and the Austrian social partners in the construction sector negotiated arrangements

to facilitate the return of foreign workers. In 2021, posting activity rose considerably compared to 2020 (+33%), while the

average number of postings also increased above the pre-pandemic 2019 level (+7%)(

49

). Furthermore, 3214 individually

posted TCNs worked in construction in 2021, and these accounted for 25% of all incoming posted TCNs(

50

). The countries

most commonly represented among the TCNs included Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo(

51

), Serbia and Türkiye(

52

).

2.3.2.2 Belgium

Belgium was a net receiving country in terms of posted workers in the construction sector. According to the ‘Cross-

Country Information System for Migration Research at the Social Administration’ declaration tool (Limosa)(

53

), the Belgian

construction sector received 87470 posted workers (63530 posted employees and 23940 self-employed persons) in 2021,

representing around 26% of total employment in the sector(

54

). As there were around a quarter of a million posted persons

reported in total, nearly one in three persons posted to Belgium was active in the construction sector, making it the most

signicant sector for incoming posted workers. These gures might be a (strong) over- or underestimation of the reality, due

to the changes made since 2017 in the declaration tool on which they are based(

55

). However, in the Belgian construction