policylab.chop.edu

POLICYLAB

EVALUATION REPORT

| FA L L 2 019

IMPROVING SCHOOL

HEALTH SERVICES

FOR CHILDREN IN

PHILADELPHIA

AN EVALUATION REPORT FOR THE

SCHOOL DISTRICT OF PHILADELPHIA

CONTENTS

2

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

4

MAIN FINDINGS

6

INTRODUCTION & RATIONALE

8

PROCESS & METHODS

10

FINDINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS

Standards of Practice

Quality Improvement

Care Coordination

Leadership

Community/Public Health

28

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

30

RECOMMENDATIONS RECAP

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

On behalf of the School District of Philadelphia

(SDP), PolicyLab, a research center at

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, conducted

an assessment and review of school health

services offered by SDP in 2019. The

assessment focused on the Offi ce of Student

Health Services and, most directly, on the role

of the school nurse. This report offers key

recommendations based on best practice and

highlights innovative practice examples from

external districts.

The body of this report is structured using

the National Association of School Nurses’

(NASN) Framework for 21st Century School

Nursing Practice (the

Framework

), which

guided the focus of the literature and practice

review and the stakeholder interview guide.

Nursing staff interviews identifi ed the

successes, challenges, and opportunities of

the school nursing role and work.

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 3

MAIN FINDINGS

FINDING 1:

School nurses and nurse leadership need greater access to data to

eciently and eectively perform job responsibilities and to facilitate

quality improvement initiatives.

SUGGESTED SOLUTIONS:

• Optimize the current electronic health record (EHR) in order to support

standardized data collection, data sharing, and timely, accessible data

aggregation and dashboarding

• Leverage school health data to support appropriate stang models

• Evaluate data-informed decision-making when completing

performance appraisals (this requires supervisory certifications

for health services leadership)

FINDING 2:

Nurse stang and support levels can be optimized to respond to the range

of school nurse responsibilities and the volume and health complexity of

the student population.

SUGGESTED SOLUTIONS:

• Use acuity analysis to build stang models that accurately predict nursing

needs and allow for eective distribution of resources

• Determine an appropriate number of substitute nurses for full-time

employment and hire accordingly via the district

• Delegate non-medical tasks to qualified nursing assistants to prioritize

school nurse time for addressing complex student health care needs while

balancing other responsibilities such as data and records management

FINDING 3:

Health-related departments and programming should prioritize

a collaborative approach to the delivery of health services.

SUGGESTED SOLUTIONS:

• Assess the current organization of health service-related departments and

programming and align where appropriate using the Whole School, Whole

Community, Whole Child (WSCC) model as a guide

• Create a resource guide that spans physical and behavioral health services to

serve as a tool for school sta who are tasked with coordinating care

• Emphasize nurse participation on interdisciplinary care teams and consider

using the current tier structure to implement school wellness committees

4 IMPROVING SCHOOL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN IN PHILADELPHIA

FINDING 4:

Health service policies and procedures should reflect current roles

and practice and be an active resource in the delivery of services.

SUGGESTED SOLUTIONS:

• Create a readily available policy manual that includes descriptions of policies

and the procedural steps required for their implementation

• Involve nurse leadership, and all appropriate stakeholders, in the creation of

student health policies

• Allocate resources to professional development for trainings specific to

policies and procedures and the nursing profession on an ongoing basis

• Cross-train school nurses and behavioral health professionals so they can

learn about each other’s fields and better understand the overlap between

physical and behavioral health

FINDING 5:

Infrastructure supports, including stang and data accessibility,

are needed for school nurses to achieve targeted population-based care,

a core tenant of school nurse practice.

SUGGESTED SOLUTIONS:

• Promote immunization compliance through nurse-initiated strategies

• Establish a standardized process and/or consistent messaging regarding

nurses’ involvement in health education and family engagement

• Implement “mass screening days” in order to assist nurses in focusing more

intentionally on individual student needs as well as larger community and

public health initiatives

• Support nurse leadership in using data to expand their focus beyond

individual students to populations with similar health concerns

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 5

INTRODUCTION & RATIONALE

In 2011, confronted with a budget defi cit of more than $700 million, the School District of

Philadelphia (SDP) downsized its nursing staff by more than 100 school nurses.

1

Since then,

however, the district has made great strides in securing school nurse staffi ng. Most public

schools in the district now follow the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommendation

of one nurse for every building, and SDP increased the number of full-time nurses it employs

from 100 in 2011 to 265 in 2019.

SDP also invested substantial resources in

building a strong school health administrative

team, which includes the addition of a medical

director, nursing director, nurse educator and

nurse coordinator. In addition to these gains, SDP

has maintained strong community partnerships,

ensuring that all children have access to services

such as dental and vision care providers on-site at

schools throughout the school year.

In the midst of this progress, and per request by

SDP leadership, PolicyLab, a research center at

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, conducted an

evaluation and review of school health services

within Philadelphia and comparable districts

with the aim of delivering a comprehensive report

refl ective of the diverse health needs of SDP

students and the multiple stakeholders involved in

the provision of care for children in Philadelphia.

In order to accomplish this, we chose to leverage

the National Association of School Nurses’

(NASN) Framework for 21st Century School

Nursing Practice, a guiding structure for districts

seeking to achieve high-quality school nurse

practice.

2

The Framework aligns with the Whole

School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC)

model that calls for a collaborative approach to

learning and health. According to WSCC, “central

to the framework is student-centered care that

occurs within the context of the students’ family

and school community.”

3

We categorized our fi ndings in this report using the

Framework’s fi ve overlapping principles: standards

of practice, quality improvement, care coordination,

leadership and community/public health.

4

6 IMPROVING SCHOOL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN IN PHILADELPHIA

FRAMEWORK FOR 21ST CENTURY SCHOOL NURSING PRACTICE

™

Principles and accompanying practice components:

STANDARDS OF PRACTICE

• Clinical Competence

• Clinical Guidelines

• Code of Ethics

• Critical Thinking

• Evidence-based Practice

• NASN Position Statements

• Nurse Practice Acts

• Scope and Standards of Practice

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

CARE COORDINATION

• Continuous Quality Improvement

• Documentation/Data Collection

• Evaluation

• Meaningful Health/Academic Outcomes

• Performance Appraisal

• Research

• Uniform Data Set

• Case Management

• Chronic Disease Management

• Collaborative Communication

• Direct Care

• Education

• Interdisciplinary Teams

• Motivational Interviewing/Counseling

• Nursing Delegation

• Student Care Plans

• Student-centered Care

• Student Self-empowerment

• Transition Planning

LEADERSHIP

COMMUNITY/PUBLIC HEALTH

• Advocacy

• Change Agents

• Education Reform

• Funding and Reimbursement

• Health Care Reform

• Lifelong Learner

• Models of Practice

• Technology

• Policy Development and Implementation

• Professionalism

• Systems-level Leadership

• Access to Care

• Cultural Competency

• Disease Prevention

• Environmental Health

• Health Education

• Health Equity

• Healthy People 2020

• Health Promotion

• Outreach

• Population-based Care

• Risk Reduction

• Screenings/Referral/Follow-up

• Social Determinants of Health

• Surveillance

ASCD and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Whole School Whole Community Whole Child: A Collaborative Approach

to Learning and Health. http://www.ascd.org/ASCD/pdf/siteASCD/publications/wholechild/wscc-a-collaborative-approach.pdf.

Published 2014. Accessed 2019.

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 7

PROCESS & METHODS

From January 2019 to July 2019, we conducted an intensive review of local and external district

school health systems, structures and operations. We reviewed documents, analyzed policies

and procedures, interviewed key informants and conducted an expansive literature review.

The literature review included position statements from professional organizations as well

as a review of academic publications using search terms related to school health and nursing

practice. An advisory committee of primary care physical, behavioral, and early childhood

experts informed our interview guides, document review protocols and policy analyses.

The internal district assessment consisted of a series of semi-structured interviews with various

stakeholders (listed on next page). External interviews with national school health leaders

identifi ed best practices and innovative examples among districts of comparable size and

student demographic. During our key informant interviews, we used standardized qualitative

interview guides developed by our interview team and PolicyLab pediatric health care content

experts, which addressed questions related to funding, data collection, behavioral health

services, care coordination, policies and procedures, professional development, evaluation and

family engagement. We recorded, transcribed and reviewed interviews for key themes. We then

used these themes and best practice standards to identify priority recommendations within each

section of this report.

8 IMPROVING SCHOOL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN IN PHILADELPHIA

INTERVIEWS

SDP Oce of Student Health Service Administrators

• Irene Kratz, Nursing Director

• Natalie Mathurin, Medical Director

• Michelle Ovington, Financial Services Assistant Director

• Lauren Reagan, Nursing Coordinator

• Shannon Smith, Nursing Coordinator

SDP School Nurses

• Badia Brown, School Nurse

• Kathleen Celio, School Nurse

• Margaret Devine, School Nurse

• Melissa Platt, School Nurse

• Barbara Tiller, School Nurse

Physical Therapist

• Carolyn Szumal, Physical Therapist

SDP Oce of Prevention and Intervention

• Lori Paster, Deputy Chief, Prevention & Intervention

SDP Guidance Counselors

• Cynthia Moore, Guidance Counselor

• Iris Parkinson-Culbreth, Guidance Counselor

National School Health Leaders:

Washington, District of Columbia

• Kristen Rowe, Manager of Health Services, District of Columbia

Public Schools

• Danielle Dooley, Medical Director for Community Aairs and

Population Health, Children’s National Health System

• Desiree De La Torre, Director of Community Aairs and

Population Health, Children’s National Health System

Austin, Texas

• Tracy Spinner, Director of Health Services, Austin Independent

School District

OFFICE OF STUDENT

HEALTH SERVICES

The primary focus of this

assessment was on the Oce

of Student Health Services,

which manages oversight of the

following functions:

• School nurses

• Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention

(CDC) Promoting

Adolescent Student

Health (PASH) grant

• Central Level

Wellness Council

• Student Health

Advisory Council

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 9

FINDINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS

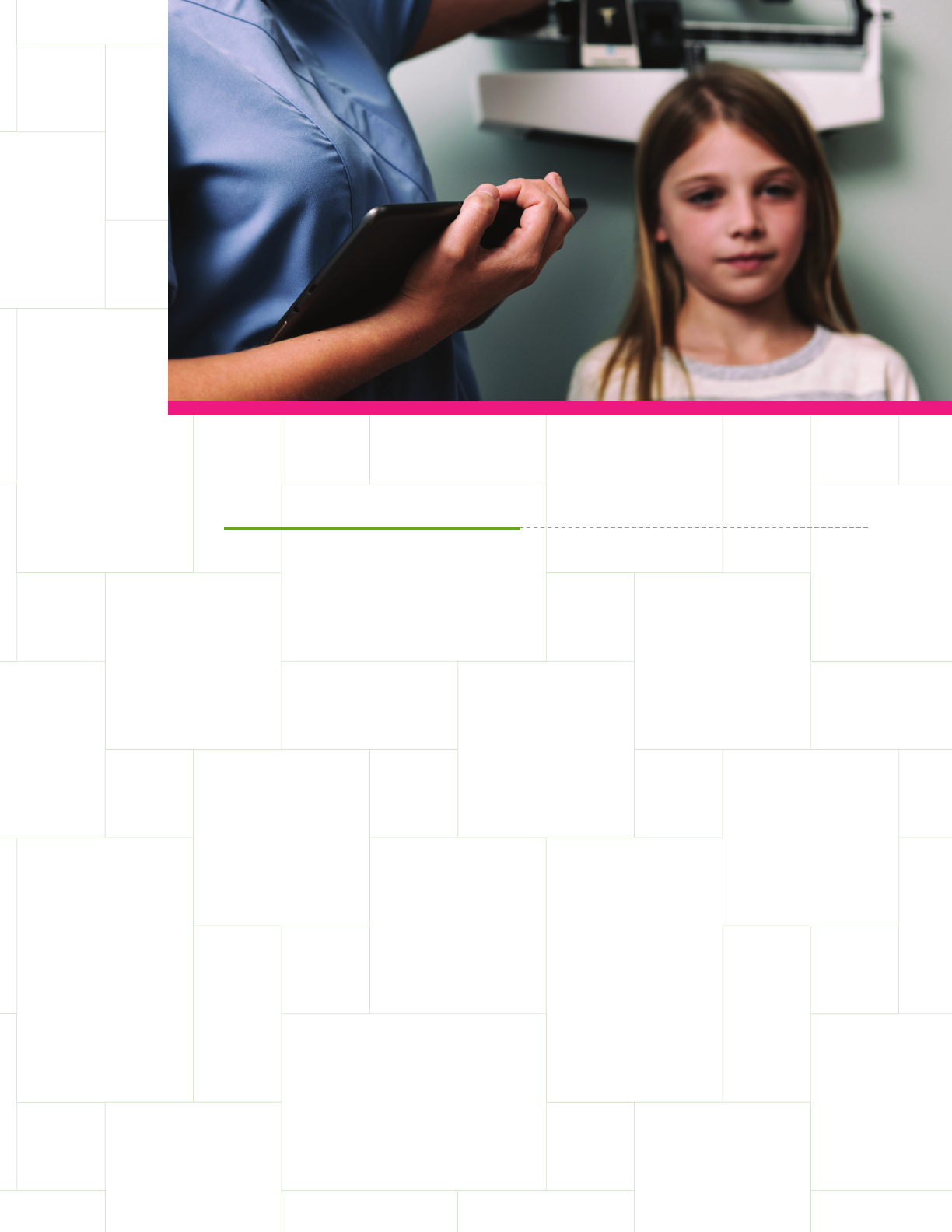

The body of this report is organized using the following principles

of the NASN Framework for 21st Century School Nursing Practice:

STANDARDS OF PRACTICE

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

CARE COORDINATION

LEADERSHIP

COMMUNITY/PUBLIC HEALTH

Denotes framework principle example from another school district

10 IMPROVING SCHOOL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN IN PHILADELPHIA

FRAMEWORK PRINCIPLE: STANDARDS OF PRACTICE

Standards of practice impact every aspect of school health services

as nurses and nursing leadership must remain up to date on both

clinical practice and policies. In this report, we highlight best practices

for school nurses with consideration of the numerous professional

organizations that issue position statements and policies aimed at

guiding school health services. For instance, in the Quality Improvement

section, we highlight important recommendations in the use of electronic

health records (EHRs), which aligns with the NASN position statement

on EHRs, and in the Community/Public Health Section, we discuss the

importance of enforcing policies for immunization compliance following

the Pennsylvania Department of Health school immunization policy and

CDC recommendations.

5–7

Best practices are reflected in each section

with additional resources for standards of practice available through

organizations such as NASN, the American Nurses Association, the

Nurse Practice Act, the CDC, the National Institutes of Health, the Food

and Drug Administration, the AAP and professional journals.

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 11

Data is the cornerstone of QI, and school nurse documentation of daily

activities is a crucial form of data collection. School nurse documentation

demonstrates the variety of roles and activities of school nurses, shows the impact

of nursing care on students’ health and identifies trends over time.

9

However,

standardization is critical for school nurse documentation to be actionable. When

districts are thoughtful about the data they choose to track and take steps to collect

and format this data in a consistent way, they are well prepared to aggregate data

across schools, identify trends and intervene appropriately.

10

Standardized data

means that every nurse across the district measures and captures the same data in

the same way.

At the individual-school level, uniform data collection could, for example,

track out-of-class time and student nurse oce visits. This could enable SDP to

monitor the use of school nurses and make quality improvements as needed in

teacher education for those who too frequently (or infrequently) send students

to the nurse or to intervene when students use the nurse’s oce for more than a

standard number of visits a year.

11

Data on student visits is particularly important

considering overutilization of the nurse’s oce could indicate underlying medical

issues. For example, “frequent flyers” who regularly come to the nurse for

unexplained headaches or stomach aches could indicate a referral to behavioral

health is necessary since somatizing children are significantly more likely than

their peers to have higher levels of depression and anxiety.

12

Not only does the literature emphasize the importance of data collection; this was

also an emerging theme during interviews. For example, interviewees indicated

a need for data collection fields within the current EHR to be more user-friendly

and for information to be more easily accessible. Additionally, interviewees noted

that the SDP EHR is not designed to provide aggregated data reports, instead

requiring long processes for requesting reports from the Oce of Information

Systems and the Oce of Research and Evaluation. Due to this limitation, nurses

and nurse leadership depend primarily on individual student reports accessible

via student health files, which does not require the tracking of health information

in a standardized way (e.g., referrals/concerns, behavioral health, most frequent

interactions). Finally, interviewees noted that they spend a substantial amount of

time locating data from multiple sources or systems and then manually inputting

data, which creates ineciencies and hinders standardization.

Quality Improvement

Recommendation Overview

• Quality Improvement

(QI) Initiatives

• Standardized Data Collection

• Electronic Health Record (EHR)

• Data Sharing

• Staffing Models

• Data & Evaluation for

Performance Appraisals

FRAMEWORK PRINCIPLE: QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

Quality improvement (QI) is an ongoing and systematic process that leads

to measurable improvements and outcomes. The NASN

Framework

aptly

describes QI as “the nursing process in action; assessment, identification

of the issue, developing a plan, implementing the plan, and evaluating

if the goals/outcomes are achieved.”

8

Creating infrastructure for data-

informed decision-making can help SDP better understand the need,

efficiency and impact of health services in real time to allow for necessary

adjustments. This section reviews how standardized data collection, data

sharing and data aggregation all contribute to a thoughtful QI program.

Additionally, we discuss the use of data to support staffing models and

performance appraisals.

12 IMPROVING SCHOOL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN IN PHILADELPHIA

To maximize the eectiveness of data collection, NASN developed a

minimum set of standardized data points that school nurses can use to track

outcomes and inform best practices.

13

Areas of data collection recommended by

NASN include: school stang levels, students with chronic conditions and health

oce visits.

14

However, for districts to use this data eectively to improve student

outcomes, they must store information in a way that is organized, easily viewable and

protective of student privacy. EHRs are an essential data collection and storage tool,

with the capacity to manage data, provide outcome analysis and share data across

settings to optimize the coordination of care.

15

RECOMMENDATION: QUALITY IMPROVEMENT (QI) INITIATIVES

We recommend allocating resources to support an increased focus

on health service QI initiatives. QI resources are foundational for

data-informed decision-making for health initiative investments

and in building the necessary infrastructure for standardizing

and using data to improve the allocation of nursing resources and

eciency of service delivery.

RECOMMENDATION: STANDARDIZED DATA COLLECTION

We recommend prioritizing several key data points for standardized

tracking that the district can use to inform QI initiatives.

NASN states that EHRs are a critical tool for not only eectively and eciently caring

for individual students, but also for monitoring student population health as a whole.

16

When properly utilized in the school setting, districts can leverage EHRs to better

understand the health needs of students, initiate quality improvement initiatives,

and improve community and family health outreach. A well-developed EHR can help

schools track their progress on improving health indicators such as vaccination rates,

and can oer quick data aggregation to improve clinical decision-making. Yet, many

educational or student data management systems are not sucient for health data

collection as these systems do not provide opportunity for documentation using medical

terminology and are often not interoperable with community-based health records.

17

Due to this limitation in student management systems, the Austin

Independent School District (AISD) developed their own EHR to track

attendance across schools as well as the most common illnesses and

injuries. They use this data to conduct trend analyses of incidents. AISD

is able to monitor immunization compliance and rates and to better

understand where children with complex health needs are clustered across

the district. AISD school nurses document their interactions directly in

the EHR, allowing them to quickly identify and act on changes in student

health trends. For example, at times when there has been an influx of

influenza, school nurses can identify the trend within 24 hours and take

actionable precautions, such as requesting that housekeeping conduct a

deep cleaning of surfaces.

AISD has also used their EHR data on a community level by monitoring kids

who initiate contact with the nursing oce due to breathing diculties.

AISD shares permissions with the local hospitals’ EHR and can track

diagnoses, action plan status, if patients are adhering to the plan and how

many times per day a student accesses their rescue inhaler. Nurse leadership

compares these numbers against community data to determine what is

usual and customary in terms of population health for that community.

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 13

A significant benefit of an optimized EHR is the ability to seamlessly view

and share data with external providers and agencies to identify trends and

improve students’ access to health services. The AAP has emphasized the

importance of collaboration between school nurses, school physicians, school sta,

families, and external pediatric providers to improve the health of children both

in school and in the community.

18

Data sharing is a critical tool for facilitating this

collaboration and, ultimately, building integrated health systems. On the school

level, data sharing with principals or the board gives administrators a clear picture

of students’ health needs and can inform decisions around stang and financing

school health programs.

19

More broadly, sharing data with external health

partners creates a more robust and triangulated view of community trends and

can help leaders identify areas in need of targeted health promotion activities.

20

In Philadelphia, nurses and nurse leadership identified an opportunity for more

readily available data in order to track trends and build models for sharing with

internal and external partners.

Washington D.C.’s public school system is an example of how school

districts can partner with state agencies to improve coordination and

service delivery. D.C. Public Schools (DCPS) developed a data sharing

agreement with the Department of Health and D.C.’s Medicaid agency.

By cross-referencing school enrollment data with Medicaid enrollment

status, dates of last well-child, dental visits, and immunization data

the three agencies have been able to identify schools with the highest

Medicaid enrollments and service utilization gaps.

21

These schools

receive targeted outreach in the form of education events and resources

for principals and school nurses to use to promote health and wellness.

22

The Department of Health Care Finance has also used the data to provide

“school health snapshots” to managed care organizations, highlighting

service usage among their DCPS-enrolled beneficiaries.

23

One challenge of data sharing is assuring that all participating data systems are

compliant with privacy requirements. The Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Federal Education Rights and Privacy Act

(FERPA) govern the release of identifiable health information and educational

records, including those collected by a school nurse. To comply with these laws,

EHR administrators must get parental or guardian permission to share student

health records and develop agreements with external providers to ensure that

student data remains confidential.

24

Oftentimes, this requires the assistance of a

legal or compliance team to review workflows ensuring EHR administrators are

meeting privacy standards.

25

On an individual level, SDP school nurses consistently expressed a desire to more

easily share information with students’ medical providers as pulling information

from student registration files can produce incomplete documentation.

Additionally, parents may not understand the depth of their child’s medical

condition, making it dicult to provide care to students without all the necessary

health information. During our interviews, nurses repeatedly identified HIPAA

and FERPA as barriers to coordination of care.

One potential solution is in simplifying and/or condensing legal consents so that

EHR administrators can design one blanket consent form for a myriad of medical and

treatment needs. Additionally, districts could create an online portal where parents

can electronically provide consent, simplifying the process. SDP could partner with

local health systems to use the site as a clearinghouse for electronic HIPAA and

FERPA signatures. This could provide easy access to needed signatures for SDP,

health systems and parents alike. Ultimately, interoperable EHRs or alternative

contractual agreements to allow for easy exchange of information are ideal.

14 IMPROVING SCHOOL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN IN PHILADELPHIA

RECOMMENDATION: ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORD (EHR)

We recommend a careful assessment of the capabilities of the current

EHR and, dependent on the outcome of that review, consideration of a

contract with a technical assistance provider for system improvements.

Dashboarding capabilities are an important component to include in

system improvements, as the ability to quickly view aggregate data is a

crucial function for health services. This may be accomplished through

the EHR or may require additional applications.

RECOMMENDATION: DATA SHARING

We recommend a review of legal and technical considerations to enable

participation in interagency data sharing or integration relationships

to improve coordination and service delivery across child-serving

systems. As a fi rst step, simplifying legal consents and the creation of an

online portal for HIPAA and FERPA consents would serve as a building

block to facilitate future data sharing arrangements.

Districts can also leverage school health data to support appropriate

sta ng models. There are numerous studies showing consistent nurse

sta ng levels are linked to improved access to care for students.

26

Research also

demonstrates that schools with lower nurse-to-student ratios are associated with

better student attendance and academic success.

27

Our interviews with SDP nurses indicated that sta ng levels can be problematic as

schools have a wide range of student population numbers and needs. Another challenge

to SDP’s current sta ng structure is nurse absenteeism, which can substantially lower

nurse sta ng levels across the district (during one day of interviews, 22 nurses called

out sick with only 4 available substitutes for the day). Interviewees also highlighted a

need for coverage during school-sponsored fi eld trips.

The district currently uses a cohort model to respond to limited numbers of

nurses and to address unlicensed professionals administering medications. The

cohort model works by placing responsibility on school nurses to coordinate and

cover for one another during times when a colleague is out of the building. For

instance, if a nurse calls out sick, nurses in the same cohort coordinate to cover

schools at certain times/hours based on need (e.g. insulin administration, asthma

treatments, etc.). Additionally, some nurses rotate through multiple schools

throughout the week.

Since 2011, SDP has made great strides in school nurse sta ng. Most district public

schools are following the AAP recommendation of one nurse for every building,

and ratios for non-public schools are close to the previously set standard of one

nurse for every 750 students. However, it is worth noting that as of 2015, NASN has

moved away from nursing ratios and toward a recommendation suggesting that

districts determine school nurse workloads annually taking into consideration

student and community health data.

28–29

As children with complex health and social needs are increasingly educated in the

mainstream classroom, school nurses play a major role in the case management,

care coordination and day-to-day health interventions required for these children

to succeed in school.

30

Nurses in Philadelphia indicated that stabilizing health

care needs for students with high social acuity can be particularly complicated and

time-consuming. For instance, SDP nurses face signifi cant barriers reconnecting

students in out-of-home placement to services when the foster family may not have

the child’s insurance information or when a prescription runs out. By using data to

A signifi cant

benefi t of an

optimized EHR

is the ability to

seamlessly view

and share data

with external

providers and

agencies to

identify trends

and improve

students’

access to health

services.

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 15

analyze school enrollment, illness and injury contacts, number of students under

ongoing case management, and health care access in the surrounding community,

schools can build models that accurately predict their nursing needs and allow for

e ective distribution of resources.

AISD has been a national leader in utilizing acuity analysis to

eff ectively distribute nursing resources among the district’s

schools.

31

In its analysis, AISD weighs a combination of medical factors,

such as number of students with complex medical conditions, alongside

community factors, such as economic disadvantage among students.

32

Additionally, the Wake County Public School System (WCPSS)

in North Carolina uses acuity analysis to establish a tiered model

through which the administration evaluates schools in the district and

sta s them at three levels depending upon student acuity/condition

and social determinants (e.g., chronic illness, medication, poverty,

language barriers, access to care). Similar to these other districts, using

community and student data to perform annual analyses could assist

SDP administrators in meeting both student and sta ng needs by

allotting nurses based on acuity instead of enrollment.

RECOMMENDATION: STAFFING MODELS

We recommend the use of community and student health data to

build models that accurately predict the district’s nursing needs

and allow for e ective distribution of resources. Additionally, to

respond to nurse absenteeism, we recommend that the district use

its own data to determine an appropriate number of substitute

nurses for full-time employment.

Evaluation is the fi nal step in the QI process. Nurse and nurse leadership should

utilize data on an ongoing basis to assess the impact of their nursing interventions on

student outcomes and determine whether processes are appropriate and e ective.

Districts should also use data for performance appraisals, incorporating

both nurses’ assessment of their own work and evaluations by a supervisor.

When evaluating nurses’ performance, supervisors should take into account the

nurses’ use of data-informed decision making. For example, a nurse may track o ce

visits and recognize a cohort of students who are accessing the nurse’s o ce far more

frequently than others. Using this data a school nurse can make determinations

about intervention (e.g., referrals to guidance or behavioral health assessment, or

discussion with a teacher). To use data in this way, it is imperative that the nursing

director and coordinators are involved in the supervision of school nurses. This

requires supervisory certifi cations for health services leadership so that the nursing

director and coordinators can directly oversee clinical supervision of school nurses.

Currently, school principals are fulfi lling this function.

The American Nursing Association and NASN recommend that all school

nurses receive clinical supervision from a registered nurse with knowledge of

school nursing practice.

33

Pennsylvania does not prohibit non-nursing sta

from supervising school nurses; the state only requires supervisors to have

As children with

complex health

and social needs

are increasingly

educated in the

mainstream

classroom,

school nurses

play a major

role in the case

management,

care coordination

and day-to-

day health

interventions

required for

these children

to succeed

in school.

16 IMPROVING SCHOOL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN IN PHILADELPHIA

an administrative credential.

34

While school administrators can continue to

supervise non-nursing tasks such as communication skills, team collaboration or

enforcement of school and district policies, non-clinical sta are not suciently

qualified to evaluate clinical nursing competency; districts should shift this

specific responsibility to nurse leadership.

35–36

Students benefit when nurse

supervisors can eectively evaluate school nurses’ responses to health care

needs and assure attention to best practices and evidence-based protocols.

Interdisciplinary evaluation and supervisory processes, inclusive of nurse

leadership and administrative sta, can also help non-clinical leadership better

understand the expansive responsibilities of school nurses.

37–38

RECOMMENDATION: DATA & EVALUATION FOR

PERFORMANCE APPRAISALS

We recommend that SDP fund supervisory certifications for health

services leadership so the nursing director and coordinators can

directly oversee clinical supervision of school nurses. This would

allow supervisors to take into account the nurses’ use of data-informed

decision-making as part of performance appraisals.

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 17

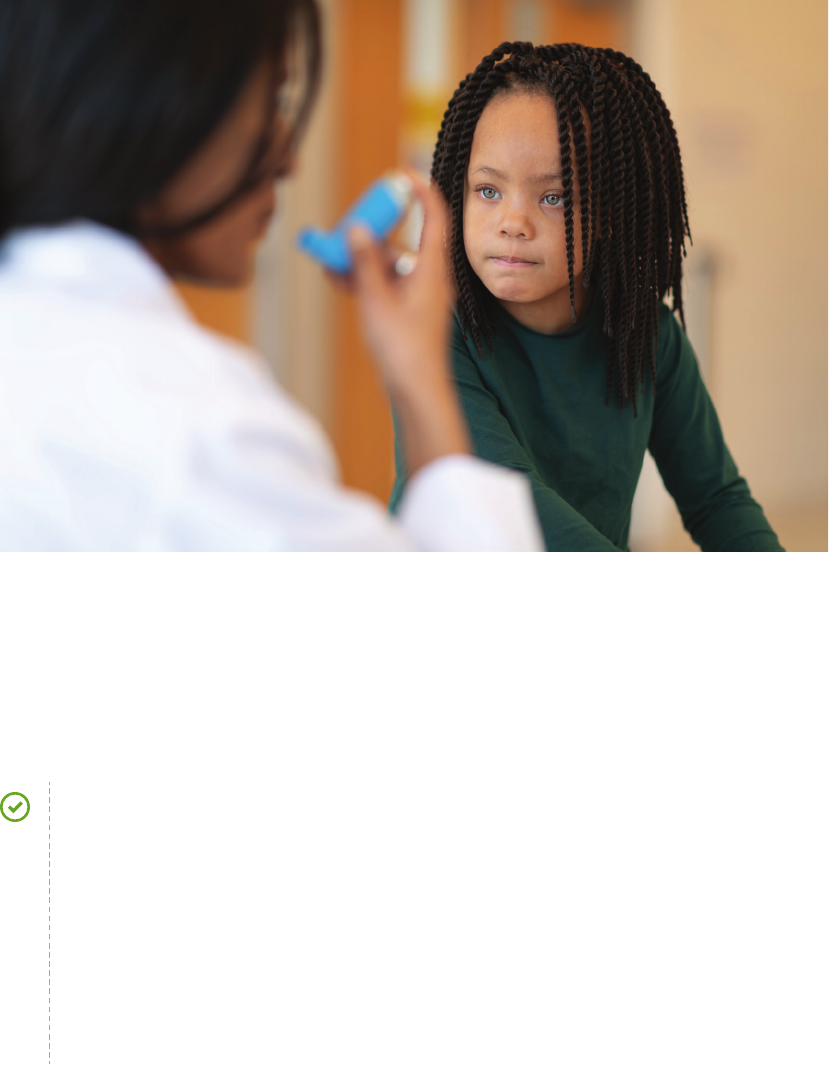

When districts are intentional in defining the role of nurses within the larger care team,

it can result in improved health outcomes for students. For example, for a student with

asthma, a school nurse may develop the child’s emergency action plan, teach school

personnel how to respond to emergencies, work with families to reduce asthmatic triggers

and teach students skills to self-manage their condition.

40

However, as evidenced by this

example, school nurses are tasked with a broad range of responsibilities beyond direct

care, including surveillance, chronic disease management, emergency preparedness,

health education, and data and records management.

41

Additionally, as chronic conditions

such as diabetes and asthma become more common and children with complex health

and social needs are increasingly educated in the mainstream classroom, school nurses

are increasingly charged with managing conditions that were previously handled in acute

care, such as tube feedings, insulin administration and emergency injections.

42

The many demands placed on a nurse require that school districts maintain

appropriate stang levels to ensure there is adequate personnel to complete

required tasks. In the QI section, we suggested the use of acuity analyses to help SDP

move away from ratios and toward the use of data to better determine needs. We also

advocated that SDP hire full-time nurse substitutes as our interviewees noted that

nursing absenteeism and lack of coverage during school-sponsored field trips lowered

nurse stang levels across the district. A third stang option is the use of delegation of

non-medical tasks to qualified health assistants.

Delegation of some nursing tasks to a qualified health assistant can help school

nurses address specific complex student health care needs while balancing other

responsibilities.

43

Health assistants are unlicensed professionals with prior health care

experience (such as EMT training), who perform basic tasks under the direct supervision

Care Coordination

Recommendation Overview

• Nurse Delegation

• Collaborative Care

FRAMEWORK PRINCIPLE: CARE COORDINATION

The broad principle of care coordination incorporates many of the daily tasks

school nurses perform and includes practice components such as student-

centered care, direct care, chronic disease management, collaborative

communication and nursing delegation.

39

During our interviews with staff,

it was clear that SDP nurses regularly engage in many of these tasks. For

example, throughout SDP, nurses are providing direct care in the form of

routine treatments, screenings, medication administration, and responses to

acute and urgent health care needs. School nurses also spoke about chronic

disease management, highlighting asthma, seizure disorders and Type 1

diabetes as critical health concerns for Philadelphia’s student population.

Nurses are well-positioned to identify children who are not achieving

their optimal level of health or academic success due to acute or chronic

medical conditions, and can develop and implement care plans that give

these students the best health, academic and quality-of-life outcomes.

Implementing structures to facilitate care coordination, such as

interdisciplinary care teams and nursing delegation protocols, can help to

manage communication between health professionals and families and

improve the efficiency of care. This section discusses coordination and

communication among partners in school health and the role and scope of

nursing responsibilities.

18 IMPROVING SCHOOL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN IN PHILADELPHIA

of the school nurse.

44

While health assistants cannot legally perform medical tasks, their

assistance with charting, record keeping and health o ce management is critical for

managing a school nurse’s workload. Health assistants can also make connections with

primary care and other external stakeholders, which nurses in Philadelphia reported as

a particular challenge when coordinating care for medically complex children. Nurses

can conduct this delegation in-person or virtually using telehealth.

AISD implemented a free, HIPPA-compliant video software called VSEE

that allows clinical assistants staff ed across the district to connect with

school nurses to diagnose and assess students over video conference. For

example, if a child comes to an assistant with a rash on their arm, the clinical

assistant can video conference with a nurse for assessment and diagnosis.

Virtual delegation can be particularly useful in districts where nurses rotate between

schools because a clinical assistant can be positioned at a school and maintain access

to the school nurse, no matter where the nurse is located. Virtual delegation can also

be utilized directly by nurses to video conference with doctors, which can reduce

unnecessary dismissals home or permit a parent to have medication prescribed

without an additional medical appointment.

45

While nursing assistants can be benefi cial in helping nurses with non-nursing

functions, it is unsafe and unwise to use health assistants in place of nursing expertise.

This is unlikely to be an issue as Pennsylvania code is fairly stringent regarding what

a school nurse is permitted to delegate to unlicensed personnel; however, the Good

Samaritan act does allow nurses to train unlicensed nursing assistants to administer

emergency medications, such as epinephrine auto-injectors and rescue asthma

inhalers.

46

Nurse delegation is a worthy consideration as many of the recommendations

made throughout this report will require substantial e ort on behalf of the school nurse

who is already concerned about how di cult it can be to accomplish all that is asked.

RECOMMENDATION: NURSE DELEGATION

We recommend that SDP delegate non-medical tasks to qualifi ed

nursing assistants to support school nurses in prioritizing

responsibilities of addressing complex health care needs while

balancing other responsibilities such as screening, medication

administration, and response to acute and urgent health care needs.

Another important factor to consider when it comes to care coordination is

interdisciplinary care teams within each school. This allows for professionals

from across disciplines—including behavioral health providers, counselors, climate

managers, special education liaisons and others—to holistically address students’

health, academic and social needs.

SDP’s monthly tier meetings help facilitate this process by bringing a diverse set of

district employees together to discuss school-wide and classroom initiatives aimed

at identifying and implementing targeted interventions. The inclusion of nurses

in these meetings in a standardized way across the district would bring important

medical context to academic or behavioral problems. For example, nurses can identify

if a child struggling in the classroom has a new or recent diagnosis and lacks access

to medication or if a child frequently visits the nurse’s o ce and could benefi t from

targeted interventions; this could ensure that all related sta are updated and receive

the same information. During these meetings, school nurses can also provide critical

perspectives on health promotion, disease prevention and care coordination. Finally,

SDP could consider how it can alter or combine the current tier meetings to create

school wellness committees, which are used in districts across the country.

Nurses are

well-positioned

to identify

children who are

not achieving

their optimal

level of health

or academic

success due

to acute or

chronic medical

conditions, and

can develop and

implement care

plans that give

these students

the best health,

academic and

quality-of-life

outcomes.

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 19

Another way that districts can ensure a collaborative approach to health

services is by providing information to sta that clearly describes the health

services and supports, including physical and behavioral health, available

for students throughout the district. Beyond their programs and role, SDP sta

were often unsure of other health services being delivered within their schools and

the district at-large, and nurses endorsed having limited involvement/collaboration

with behavioral health services in particular. One thing that may contribute to this

is that SDP health-related o ces are currently separated into di erent departments,

which can create barriers to information sharing. For example, health and physical

education, food services and health programming, such as Eat Right Philly, all relate

to health, but are not unifi ed under a common department or o ce. This separation

makes regular and collaborative communication a top priority—an issue that SDP

nurses raised throughout our interviews. There are several possible solutions:

• Realignment of health service-related departments within SDP

• A resource guide, which can serve as a tool for sta tasked with

coordinating care, and is also informative for anyone seeking to

understand the work originating from this o ce. The Los Angeles

Unifi ed School District (LAUSD) off ers a useful example in their

Health and Human Services Resource Guide, which outlines

available services, resources and partnerships under the Health

and Human Services umbrella and includes program descriptions,

types of service and contact information for each department

(e.g., Department of Diversity and Equity, pupil services, school

mental health and restorative justice.)

47

• A principal’s guide, which is a potentially more granular way to

educate sta and principals. DCPS created a principal’s guide

to school health, which includes descriptions of key concepts

regarding laws and regulations and dictates many of the

procedures that staff must follow as a result.

All of these serve as useful examples for how principals, colleagues and other

departments can better understand health services work and more clearly

delineate points of connection, communication and collaboration.

RECOMMENDATION: COLLABORATIVE CARE

We recommend that SDP ensure a collaborative approach to health

services by:

• Assessing the current organization of health service-related

departments and programming and aligning where appropriate

using the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC)

as a guide

• Creating a resource guide that spans physical and behavioral health

services and provides information to sta that clearly describes the

available health services and supports

• Emphasizing nurse participation on interdisciplinary care teams

and considering the creation of school wellness committees using

the current tier structure

Interdisciplinary

care teams allow

for professionals

from across

disciplines to

holistically

address students’

health, academic

and social needs.

20 IMPROVING SCHOOL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN IN PHILADELPHIA

Clear and eective policies and procedures are integral to school health

services. Policies not only inform and support school personnel, but reassure key

stakeholders that schools are addressing health and safety issues.

49

Throughout

interviews, school nurses were inconsistent with their understanding of health

services policies. Nurses often referenced state mandated requirements when

asked about district-wide policies and procedures, and some interviewees

indicated that current policies and procedures are significantly outdated with

reference to a policy manual last updated in the 1990s. Policies can play a major

role in changing school culture; therefore, it is essential that school nurses have a

readily available policy manual including a description of the policy, procedural

steps to implement the policy, a method of tracking the implementation of the

policy and an eective way to enforce the policy.

School nurses and nurse leadership are vitally important to the development

and implementation of health policies, programs and procedures, and should

be included in the development of policies specific to their role.

50

Staying up

to date on relevant research, position statements and professional education is one

of the key roles for nurse leadership and ensures that policies are reflective of best

practice.

51

School nurses are also best-positioned to ensure that school health policies

align with state and federal regulations. Finally, nurse leaders can utilize health

services data to recognize trends or issues that provide opportunities for policy

development. For instance, the rate of epinephrine administration for students

who are undiagnosed with an allergy could prompt a policy recommendation that

requires a stocked supply of epinephrine in each building.

52

Without including feedback from those trained and experienced in school nursing,

administrators can enact policies that are overly cautious or in direct violation

to nurse recommendations. For example, the Oce of Safety has a policy that

requires school personnel to call an ambulance for all students who are found to

have smoked marijuana or have been sprayed with pepper spray, rather than having

the nurse first evaluate the student to determine the appropriate need for care.

FRAMEWORK PRINCIPLE: LEADERSHIP

Leadership is an essential mindset for school nurses. According to

NASN, as the only medically trained professional in the school setting,

school nurses are well-positioned to take a leadership role, specifically,

in the development and implementation of health policies, programs,

and procedures.

48

This ensures the centrality of health services in the

educational setting, and is a best practice in terms of defining the

structure of health service programming and providing guidance for

staff in delivering optimal care. This section will address both policies/

procedures and professional development, two activities that are

closely related and represent key components in nursing leadership.

Leadership

Recommendation Overview

• Policies & Procedures

• Professional Development

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 21

There are several online tools that SDP could fi nd useful as it considers revisions to

its policy manual:

• An online course designed by the AAP via the TEAMs project. This resource

o ers a guide to school districts as they plan and implement health service

improvements. The course highlights the development of health service

policies and protocols and o ers guidance on policy development.

• The CDC’s School Health Policies and Practices Study (SHPPS). This national

survey covers student health records, school entry requirements, required

immunizations, procedures for student medications and more. It could be

a useful starting place for developing a framework of needed policies and

procedures.

• The Central Level Wellness Committee, newly led by the O ce of Student

Health Services. This body can serve as a useful resource in ensuring that

policies are developed and revised in accordance with best practice and with

input from a diverse audience.

RECOMMENDATION: POLICIES & PROCEDURES

We recommend that school nurses have a readily available policy

manual including descriptions of the policies and procedural steps

needed to implement. Additionally, we recommend engagement from

all necessary stakeholders in policy creation. SDP should also utilize

the Central Level Wellness Committee as a venue for collaborative

communication regarding nursing practice and procedure.

Professional development is another important consideration as professional

development and networking opportunities are infrequent. School nurses often

work in isolation, sometimes as the sole health care provider in a building caring

for students with a broad scope of health care needs.

53–54

Professional isolation in

the school setting can limit nurses’ exposure to tools or changes in care practices,

making education an important priority.

55–56

Additionally, professional development

can ensure that nurses are aware of new or updated policy and procedures and

that they have the knowledge and skills to carry them out. During sta interviews,

nurses highlighted the intention to hire a nurse educator to support professional

development and provide personalized performance coaching and mentorship.

To support this new role, SDP may consider providing professional development

resources so the nurse educator can attract speakers who can grant continuing

education units (CEUs) or is able to teach continuing education classes themselves,

which could include access to e-learning software or videoconferencing capabilities.

Utilizing online learning modules can be an effi cient way to get

nurses the education they need, when they need it. AISD uses the Safe

Schools Platform to automate sta training. This platform allows the

district to purchase required trainings, such as basic illness and injury,

suicide prevention, anaphylaxis and medication management, while also

developing their own. With this platform, the district can be responsive to

both regulations and the interest of their nurses. It also allows the district

to provide trainings on an ongoing basis throughout the school year.

Professional

isolation in the

school setting

can limit nurses’

exposure to tools

or changes in

care practices,

making

education an

important

priority.

Professional

development

can ensure

that nurses are

aware of new or

updated policy

and procedures

and that they

have the

knowledge and

skills to carry

them out.

22 IMPROVING SCHOOL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN IN PHILADELPHIA

Another important factor to consider when developing training for nurses

and other sta members is the need for cross training in behavioral health.

School nurses are often the first to interface with students experiencing behavioral

and mental health challenges, including bullying, school phobia, anxiety, and stress-

related physical symptoms such as stomach pain and headaches. It is recommended

that school nurses and behavioral health professionals cross train to learn about each

other’s fields and better understand the overlap between physical and behavioral

health and the impact of chronic medical conditions on psychosocial functioning.

District-led training should oer mental health topics to school nurses, including

eective responses to suicidal concerns, behavioral health crisis management,

indicators of behavioral health problems, anxiety and depression. School nurse

training should be trauma-informed and culturally responsive.

57–58

The WSCC approach recommends that schools and communities have shared

learning experiences to develop common terminology and approaches to best meet

the needs of students.

59

Using an online platform is an eective way to ensure that

diverse audiences have access to relevant training materials.

RECOMMENDATION: PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

We recommend the allocation of resources for professional

development activities to include visiting speaker presentations

with continuing education units (CEUs) and/or the procurement

of software for e-learning or videoconferencing capabilities.

Additionally, we recommend routine cross-training for school

nurses and behavioral health professionals.

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 23

Throughout interviews, there was wide concern regarding immunizations

and the lack of school entry requirements.

61

Immunizations are a critical public

health intervention as they help to protect the health of the entire community.

High percentages of unvaccinated individuals can lead to local outbreaks and

spread contagious illnesses to vulnerable populations, including those who cannot

be immunized for age or medical reasons.

62

School nurses play a significant role in

surveillance and outreach eorts and can make a substantial impact on the rates of

compliance within communities.

It is NASN’s position that promotion of immunizations is central to the public health

focus of school nurses and that school nurses are well-positioned to create awareness

and influence action.

63

School nurses play an important role in risk reduction by

providing strong recommendations and addressing misconceptions through outreach

and education. Evidence-based immunization strategies include hosting vaccination

clinics in schools, providing vaccine education, sending reminders about vaccine

schedules, and using state information systems for accessing and sharing accurate

information with families who may not have access to up-to-date records.

64

One study, in a Northern Indiana High School, found that using a three-step, nurse-

initiated process to increase immunization compliance was highly successful. In the

first step, nurses sent letters home to notify parents who were not in compliance with

state law. They followed this up with a second letter providing information from the

Community/Public Health

Recommendation Overview

• Immunizations

• Health Education/

Parent Engagement

• Routine Screening/

Population-based Care

FRAMEWORK PRINCIPLE: COMMUNITY/PUBLIC HEALTH

School nurse practice is grounded in community and public health.

Throughout interviews we heard how public health concerns impact

a school nurse’s day-to-day work, and the health risks that students

face due to environmental exposures both at home and at school.

Some nurses spoke about breathing difficulties and the environmental

concerns that contribute to the broader issue, including exposing

children to mold, rodents or asbestos.

Interviewees also indicated a desire to track data to better

target population-based care. AISD has been intentional

about this work by creating geographic information system

(GIS) maps that layer information collected by school nurses.

Using this data they are able to determine by geographic

location which schools have the highest rates of asthma.

They identified the I-35 corridor as a problematic area, so the

district installed improved HVAC filters in the schools with

closest proximity. This is a useful example of how school

health services can expand their focus beyond the individual

student to populations with similar health concerns.

Ultimately, school nurses play a significant role in population health

through efforts at disease prevention and health promotion, two core

functions of public health.

60

In this section, we highlight several key

disease prevention and health promotion activities.

24 IMPROVING SCHOOL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN IN PHILADELPHIA

health department about needed vaccinations, the importance of disease prevention

and contact information for appointments. If needed, nurses sent a third letter home

coupled with a phone call to parents. All communications included exclusion dates and

an explanation of what exclusion means. Prior to this intervention, 34% of the student

population would have been excluded from attendance in the event of an outbreak

of a vaccine-preventable disease. After implementation, less than 1% of the school

population would have missed class time.

65

A compelling local example is that of a SDP nurse coordinator and principal who

worked together to inform parents, at one school, of the school entry requirement,

setting a date for exclusion for children with no vaccine records. They identifi ed

13 children at the onset of the e ort; however, with regular outreach, support

and follow-up only two children were left unvaccinated by the deadline. This

shows not only how proactive outreach and education are crucial to engaging and

connecting parents with care, but also how addressing noncompliance with school

enforcement can increase immunization rates.

66

RECOMMENDATION: IMMUNIZATIONS

We recommend the creation of a district-wide, nurse-initiated

vaccine compliance strategy to include education, reminders and

exclusion when necessary.

School nurses play an important role in health promotion by addressing

misconceptions through outreach and education. This is true for

immunization compliance and is also applicable to other topics. As an example,

nurses reported that not all parents of SDP children with health conditions have

a clear understanding of the child’s condition. School nurses are well-poised to

provide community health education through o ering parent night topics covering

common medical conditions or, on a broader scale, topics such as environmental

concerns and healthy environments. In addition to addressing an important health

education function, these family education events could also increase family

engagement with health services, an important component of WSCC.

67

Not only are school nurses poised to o er community education, but they can

provide important health education to students. Some SDP nurses spoke of o ering

student health education while others felt unable to do so due to time constraints.

A standardized process for health education or consistent messaging about

nurses’ involvement in such activities may be useful. Using a needs assessment to

determine areas of focus for community or student education can be a useful fi rst

step in the development process.

68

The Student Health Advisory Council, which is

newly led by the O ce of Student Health Services, could serve as a useful resource

in developing a needs assessment as well as reviewing and developing curriculum.

This advisory council includes experts from the medical fi eld who can provide a

wide perspective about prevalence of needs, making the council well-positioned to

identify areas of emphasis for health promotion activities.

RECOMMENDATION: HEALTH EDUCATION/PARENT ENGAGEMENT

We recommend the creation of a standardized process for

nurse involvement in health education and family engagement.

SDP should utilize the Student Health Advisory Council as a

venue for expert consultation.

School

nurses play a

signifi cant role

in population

health through

e orts at disease

prevention

and health

promotion, two

core functions

of public health.

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 25

Another important disease prevention and health promotion activity

supported by school nurses is that of ensuring student health through routine

screening. Routine screening allows school nurses to identify need and connect

children and families with necessary care. Pennsylvania public school code requires

certain health screenings for all children (dental, vision, hearing, height and weight,

etc.).

69

A suggestion made repeatedly by the nurses we interviewed was that of a

“mass screening day,” during which nurses could complete routine screenings all at

once. Nurse’s spoke of being pulled in many direction throughout the day, and how

urgent health care needs, medication changes, parent visits and injuries can take

precedent over completing screenings. A mass screening day would allow nurses to

identify children in need of services early in the school year, providing ample time

to complete consents for those at risk for hearing or vision loss or for those who need

access to glasses or dental exams.

This early identifi cation could support nurses in focusing on coordination of care

and in assisting children who are at-risk in accessing needed treatments. SDP

currently has a robust array of community partnerships, such as the Eagles Eye

mobile and St. Christopher’s dental van. These partnerships complement the

work of the school nurse by providing an easily accessible referral site for students

who are in need of oral, vision or hearing services. Collaboration and networking

with community partners facilitates e ective care and is a best practice central

to WSCC.

70–71

However, to make the most of these partnerships, nurses must have

screenings and consents complete prior to visits by these mobile providers so that

partners can focus on providing needed treatment services.

Some districts tackle the task of mass screenings by using nurses from other

schools who can be available for most or part of a day or through partnership

with volunteer health providers. SDP could consider using nurses within cohorts,

enlisting substitute nurses or engaging community partners to rotate throughout

schools—some community partners have expressed interest in screening as it

provides a useful opportunity to train residents within their program. It may also

be useful to prioritize schools with highest enrollment or greatest acuity when

considering how to best organize mass screening days. Supporting nurses in

completing screenings early in the school year could free up nurse time to focus

more intentionally on individual student needs as well as larger health promotion

and disease prevention activities.

A targeted example of this is LAUSD’s application of a public health

model to address oral health. The district implemented this program in

response to routine screenings and signifi cantly reduced the number of

students across the district with active dental disease.

72

Another example gleaned throughout interviews was in relation to

population-based care and a desire to expand the focus of nurses to include

groups of students with similar health concerns. One example is in caring

for students with asthma, which is a substantial health concern for Philadelphia

communities. Tracking data on attendance could help nurses to identify children

with asthma who are absent more than typically expected. They could use this

information to follow-up on causality—weather changes, lack of maintenance

inhalers or a need for a primary care physician. Nurses could use this information

to connect families with needed services and target areas for health promotion

and education for whole communities.

Supporting

nurses in

completing

screenings early

in the school

year could free

up nurse time

to focus more

intentionally

on individual

student needs

as well as

larger health

promotion

and disease

prevention

activities.

26 IMPROVING SCHOOL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN IN PHILADELPHIA

There are numerous illustrations of public health approaches that can be

undertaken by the Oce of Health Services, and it is our hope that the

recommendations made throughout this report will provide the foundation

that is necessary for nurses and nurse leadership to become more involved in

community and public health initiatives.

RECOMMENDATION: ROUTINE SCREENING/

POPULATION-BASED CARE

We recommend a review of the logistical and resource considerations

required for the implementation of “mass screening days” as a

population-based intervention strategy for systems-level eciency.

Within a system that supports mass screening interventions, nurses

may allocate a higher percentage of their time toward individual student

needs and larger community and public health initiatives. We also

recommend that SDP support nurse leadership in using data to assess

and identify core student and community populations who may benefit

from targeted services and/or increased health promotion activities.

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 27

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The health of students is

critically important for their

educational engagement and

attainment and can help put

them on a path to a successful

future. The School District

of Philadelphia has a strong

foundation for school health

services and a talented

workforce of school health

nurses and administrators.

The opportunities outlined

in this report to improve the

delivery of health services

will enhance alignment with

best practice and advance

the use of data, technology

and capacity for quality

improvement.

28 IMPROVING SCHOOL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN IN PHILADELPHIA

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR THIS WORK COULD INCLUDE FURTHER EXPLORATION OR

CONSULTATION ON RECOMMENDATIONS MADE THROUGHOUT THIS REPORT, INCLUDING:

Using data to

improve processes

Exploring how to legally

permit a more effective

exchange of information

between school and external

health professionals

Utilizing telehealth

technology both to provide

additional support to nurses

and expand services

OTHER AREAS FOR FURTHER ASSESSMENT COULD INCLUDE:

A review of behavioral health

services and how they

intersect with SDP student

health and wellness

School-based health centers

and the utility and impact of

their presence throughout

Philadelphia

The effect of care

coordination for children

with medical complexity

How to best support

parenting teens and

youth in foster care

The accessibility of

language access services

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 29

RECOMMENDATIONS RECAP

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT (QI) INITIATIVES

We recommend allocating resources to support an increased focus on health

service QI initiatives. QI resources are foundational for data-informed

decision-making for health initiative investments and in building the necessary

infrastructure for standardizing and using data to improve the allocation of

nursing resources and eciency of service delivery.

STANDARDIZED DATA COLLECTION

We recommend prioritizing several key data points for standardized tracking that

the district can use to inform QI initiatives.

ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORD (EHR)

We recommend a careful assessment of the capabilities of the current EHR and,

dependent on the outcome of that review, consideration of a contract with a

technical assistance provider for system improvements. Dashboarding capabilities

are an important component to include in system improvements, as the ability to

quickly view aggregate data is a crucial function for health services. This may be

accomplished through the EHR or may require additional applications.

DATA SHARING

We recommend a review of legal and technical considerations to enable

participation in interagency data sharing or integration relationships to improve

coordination and service delivery across child-serving systems. As a first step,

simplifying legal consents and the creation of an online portal for HIPAA and

FERPA consents would serve as a building block to facilitate future data sharing

arrangements.

STAFFING MODELS

We recommend the use of community and student health data to build models that

accurately predict the district’s nursing needs and allow for eective distribution

of resources. Additionally, to respond to nurse absenteeism, we recommend that

the district use its own data to determine an appropriate number of substitute

nurses for full-time employment.

DATA & EVALUATION FOR PERFORMANCE APPRAISALS

We recommend that SDP fund supervisory certifications for health services

leadership so the nursing director and coordinators can directly oversee clinical

supervision of school nurses. This would allow supervisors to take into account the

nurses’ use of data-informed decision-making as part of performance appraisals.

NURSE DELEGATION

We recommend that SDP delegate non-medical tasks to qualified nursing assistants

to support school nurses in prioritizing responsibilities of addressing complex

health care needs while balancing other responsibilities such as screening,

medication administration, and response to acute and urgent health care needs.

30 IMPROVING SCHOOL HEALTH SERVICES FOR CHILDREN IN PHILADELPHIA

COLLABORATIVE CARE

We recommend that SDP ensure a collaborative approach to health services by:

• Assessing the current organization of health service-related departments and

programming and aligning where appropriate using the Whole School, Whole

Community, Whole Child (WSCC) as a guide

• Creating a resource guide that spans physical and behavioral health services

and provides information to sta that clearly describes the available health

services and supports

• Emphasizing nurse participation on interdisciplinary care teams and considering

the creation of school wellness committees using the current tier structure

POLICIES & PROCEDURES

We recommend that school nurses have a readily available policy manual

including descriptions of the policies and procedural steps needed to implement.

Additionally, we recommend engagement from all necessary stakeholders in policy

creation. SDP should also utilize the Central Level Wellness Committee as a venue

for collaborative communication regarding nursing practice and procedure.

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

We recommend the allocation of resources for professional development activities

to include visiting speaker presentations with continuing education units

(CEUs) and/or the procurement of software for e-learning or videoconferencing

capabilities. Additionally, we recommend routine cross-training for school nurses

and behavioral health professionals.

IMMUNIZATIONS

We recommend the creation of a district-wide, nurse-initiated vaccine compliance

strategy to include education, reminders and exclusion when necessary.

HEALTH EDUCATION/PARENT ENGAGEMENT

We recommend the creation of a standardized process for nurse involvement in

health education and family engagement. SDP should utilize the Student Health

Advisory Council as a venue for expert consultation.

ROUTINE SCREENING/POPULATION-BASED CARE

We recommend a review of the logistical and resource considerations required for

the implementation of “mass screening days” as a population-based intervention

strategy for systems-level eciency. Within a system that supports mass screening

interventions, nurses may allocate a higher percentage of their time toward

individual student needs and larger community and public health initiatives. We

also recommend that SDP support nurse leadership in using data to assess and

identify core student and community populations who may benefit from targeted

services and/or increased health promotion activities.

EVALUATION REPORT | FALL 2019 31

AUTHOR

Shawna Dandridge, LCSW, is the behavioral

health strategy manager at PolicyLab at

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Advisory committee of PolicyLab pediatric

health care content experts:

Tyra Bryant-Stephens, MD

Ahaviah Glaser, JD

Meredith Matone, DrPH, MHS

David Rubin, MD, MSCE

Jami Young, PhD

PolicyLab sta who provided research

and editorial contributions:

Linda McWhorter, PhD

Madeline O’Brien, MPA

PARTNER

PolicyLab thanks the School District of

Philadelphia (SDP) for partnering on this

report. In particular, we want to recognize the

administrators of the Oce of Student Health

Service for their participation, enthusiasm and

support throughout this project. We are also

grateful to the various stakeholders within SDP

who participated in interviews—school nurses,

guidance counselors, physical therapists and

members of the SDP leadership team—as well as

the national school health leaders we interviewed

from external districts.

SUGGESTED CITATION

Dandridge S. Improving School Health Services

for Children in Philadelphia: An Evaluation Report

for the School District of Philadelphia. PolicyLab