Using Behavioral Science

to Improve Criminal Justice

Outcomes

Preventing Failures to Appear in Court

Brice Cooke

Binta Zahra Diop

Alissa Fishbane

Jonathan Hayes

Aurelie Ouss

Anuj Shah

November 2017

USING BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE TO IMPROVE CRIMINAL JUSTICE OUTCOMES 2

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur

Foundation, and the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) for their early and continued

support of this work. We are also greatly appreciative for the support and close partnership with

the New York City Mayor’s Oce of Criminal Justice, in particular Elizabeth Glazer, Alex Crohn, Allie

Meizlish, and Angela LaScala-Gruenewald; the New York City Police Department, in particular Deputy

Commissioner Susan Herman, Detective Kenneth Rice, and Lieutenant Denis O’Hanlon; and the New

York State Unified Court System Oce of Court Administration, in particular Justin Barry, Jason Hill,

Karen Kane, Carolyn Cadoret, and Zac Bedell.

We also would like to thank our colleagues at ideas42 and the University of Chicago Crime Lab and

especially Roseanna Ander, Katy Brodsky Falco, Chelsea Hanlock, Zachary Honoro, Christina Leon,

and Jens Ludwig for their invaluable assistance, Christina Avellan, Hannah Furstenberg-Beckman,

and Jessica Leifer for their contributions to the diagnosis and designs of the text message reminders,

and Ethan Fletcher, Jaclyn Leowitz, David Munguia Gomez, and Allison Yates-Berg for their contri-

butions to the summons form re-design.

The views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those

of any funders or data providers.

Contact: Alissa Fishbane (alissa@ideas42.org) or Aurelie Ouss (aouss@sas.upenn.edu)

USING BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE TO IMPROVE CRIMINAL JUSTICE OUTCOMES 3

About ideas42

We’re a leader in our field with unique expertise and experience at the forefront of behavioral science.

We use this to innovate, drive social change, and improve millions of lives. We create fresh solutions

to tough issues based on behavioral insights that can be scaled up for the greatest impact. ideas42

also educates leaders and helps institutions improve existing programs and policies.

Our work spans 30 countries and encompasses consumer finance, economic mobility, education,

energy and the environment, health, international development, and safety and justice. As a global

nonprofit organization, our partners include governments, foundations, companies, NGOs, and many

other institutions.

At its core, behavioral science helps us understand human behavior and why people make the

decisions they do. It teaches us that context matters, that asking the right questions is critical, and

that simple solutions are often available, but frequently overlooked or dismissed. We work to identify

the subtle but important contextual details that can have a disproportionate impact on outcomes.

Visit ideas42.org and follow @ideas42 on Twitter for more.

About the University of Chicago Crime Lab

The U.S. has the highest rate of homicide among any developed nation in the world. The U.S. also

has by far the highest rate of incarceration among any high-income nation, with over 2.2 million

people currently incarcerated nationwide. Both of these problems disproportionately aect our most

economically disadvantaged and socially marginalized communities.

Taken together, all levels of government in the U.S. spend well over $200 billion per year on the

criminal justice system (including police, courts, and corrections). Yet we have made little long-term

progress on these problems. The homicide rate in America today is about the same as it was in 1950,

or even 1900. This stands in stark contrast to the enormous progress the U.S. has made toward

reducing mortality rates from almost every other leading cause of death. One key reason we have not

made more progress on these problems is a striking lack of rigorous evidence about what actually

works, for whom, and why.

The University of Chicago Crime Lab and sister organization Crime Lab New York aim to change

this by doing the most rigorous research possible in close collaboration with city government and

non-profits. Using randomized controlled trials, insights from behavioral economics, and predictive

analytics, the Crime Lab partners with government agencies and frontline practitioners to design

and test promising ways to prevent violence and reduce the social harms of the criminal justice

system, with the ultimate goal of helping the public sector deploy its resources more eectively (and

humanely) to improve lives.

Building on the model of the Crime Lab, the University of Chicago launched Urban Labs in 2015 to

help cities identify and test the policies and programs with the greatest potential to improve human

lives at scale. Under the direction of leading social scientists, Urban Labs utilizes this approach across

five labs that tackle urban challenges in the crime, education, energy & environment, health, and

poverty domains.

Visit urbanlabs.uchicago.edu/labs/crime

Executive Summary

I

n 2014, nearly 41% of the approximately 320,000 cases from tickets issued to people for low-level

oense in New York City (NYC) had recipients who did not appear in court or resolve their summons

by mail. This represents approximately 130,000 missed court dates for these oenses. Regardless of

the oense severity (summonses are issued for oenses ranging from things like riding a bicycle on

the sidewalk to drinking in public), failure to appear in court automatically results in the issuance of an

arrest warrant. Because warrants are costly and burdensome for both the criminal justice system and

recipients, the NYC Mayor’s Oce of Criminal Justice—in partnership with the New York City Police

Department and New York State Unified Court System Oce of Court Administration—asked ideas42

and the University of Chicago Crime Lab to design and implement inexpensive, scalable solutions to

reduce the failure to appear (FTA) rate.

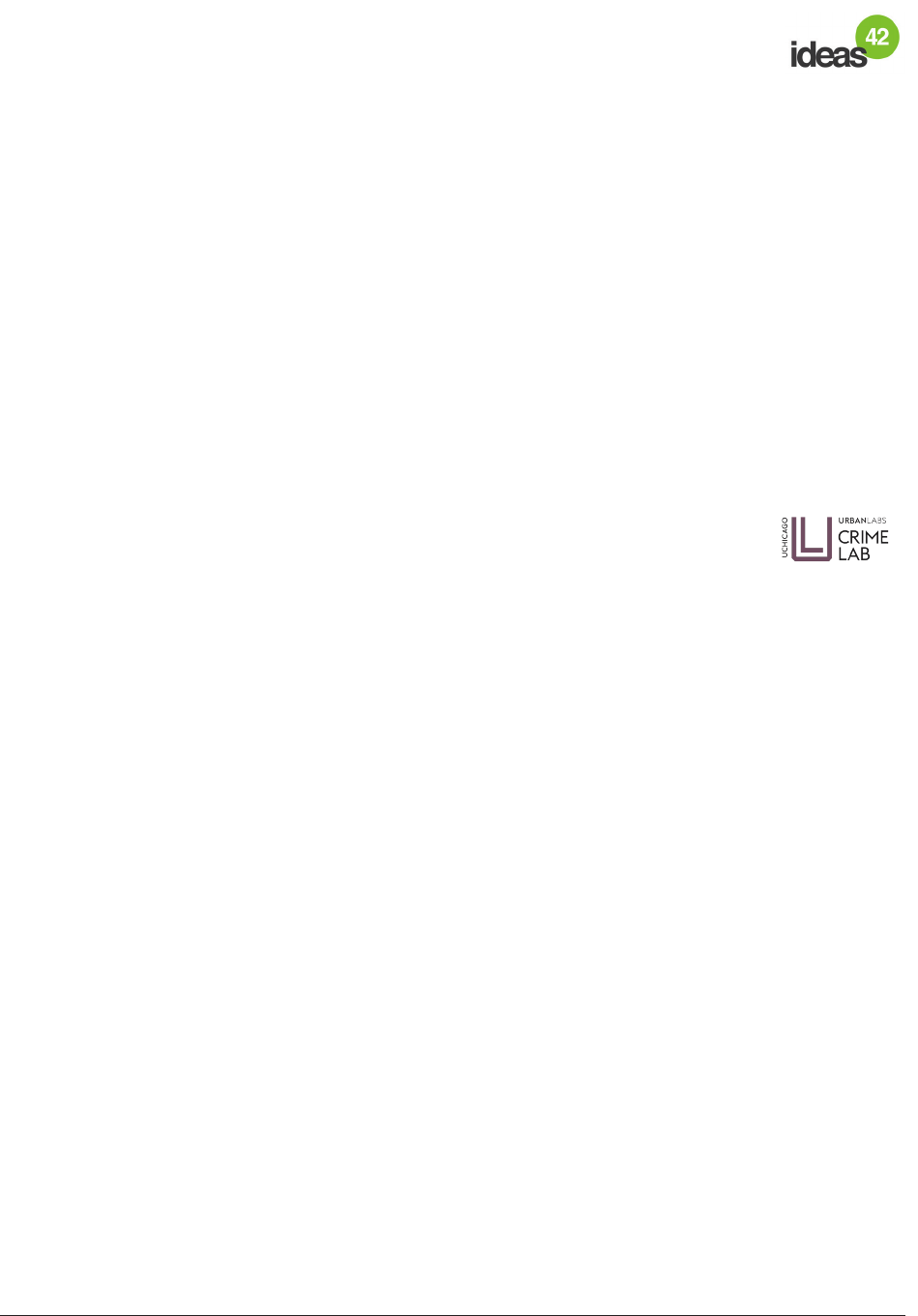

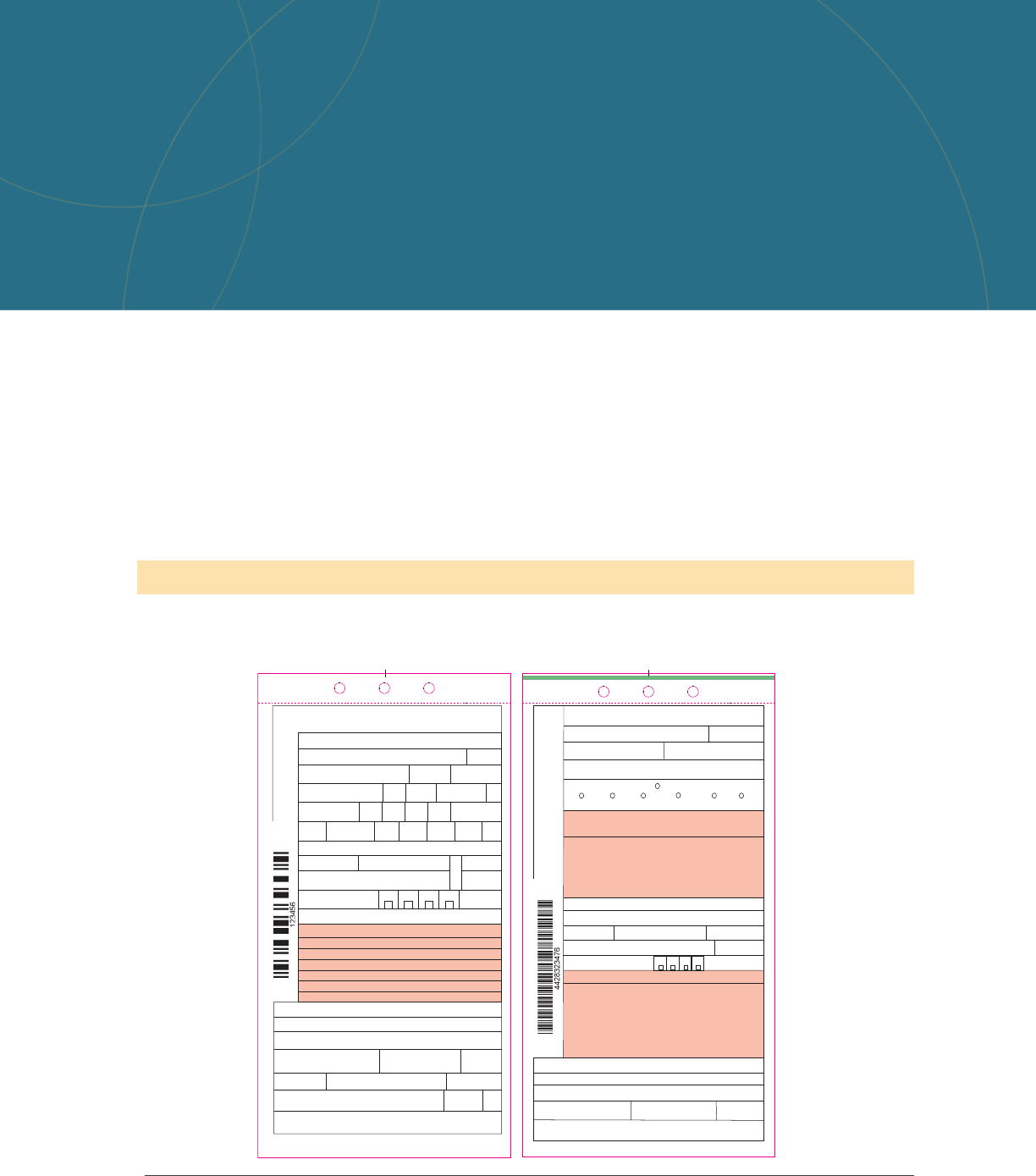

We tackled this problem using a two-sided approach. First, we re-designed the NYC summons form

to make the most relevant information stand out, making it easier for people to respond appropriately.

In the new form, important information about one’s court date and location is moved to the top, the

negative consequence of failing to act is boldly displayed, and clear language encourages recipients

to show up to court or plead by mail.

Second, we created text message reminders. We identified behavioral barriers leading many to

miss their court dates: people forget, they have mistaken beliefs about how often other people skip

court, they see a mismatch between minor oenses and the obligation to appear in court, and they

overweigh the immediate hassles of attending court and ignore the downstream consequences. We

then designed dierent reminders targeted at helping recipients overcome these barriers.

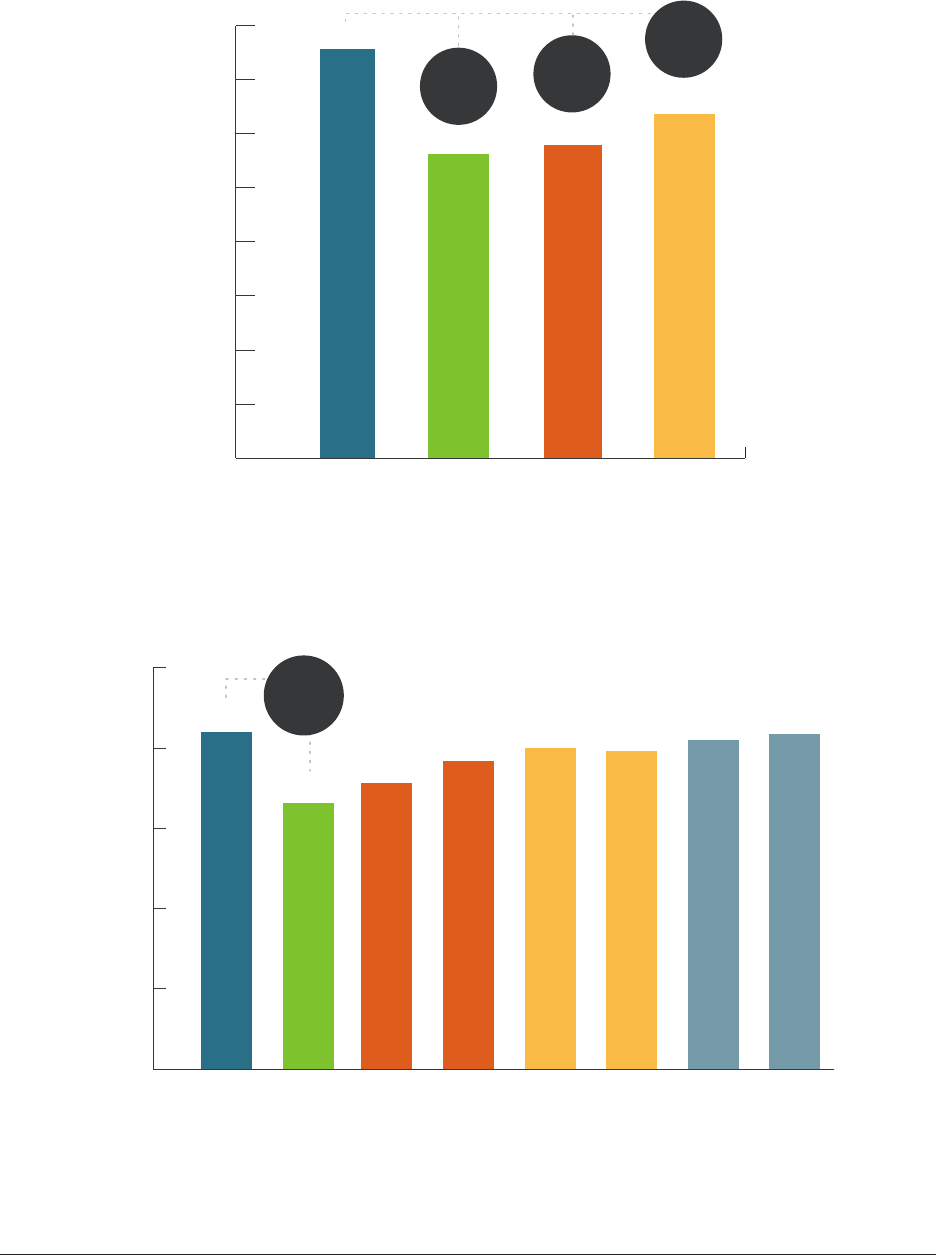

From March 2016 to September 2017 we implemented and evaluated our interventions, and showed

that both have significant and positive eects on appearance rates. We found that behavioral

re-design of the form reduced FTA by 13%. has already been scaled system-wide to all criminal

court summonses, and, based on 2014 figures, translates to preventing roughly 17,000 arrest warrants

per year.

Using a randomized controlled trial, we found that the most eective reminder messaging reduced

FTA by 26%, relative to receiving no messages. Looking 30 days after the court date, the most

eective messaging reduced open warrants by 32% relative to receiving no messages. This stems

from both reducing FTA on the scheduled court date as well as court appearances after the FTA

to clear the resulting warrant. These results are in addition to the gains already realized from the

summons form re-design. The most eective messaging combined information on the consequences

of not showing up to court, what to expect at court, and plan-making elements.

USING BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE TO IMPROVE CRIMINAL JUSTICE OUTCOMES 5Executive Summary

Traditionally, criminal justice policy is informed by the assumption that people make an explicit decision

to oend, and so most approaches aim to make crime less worthwhile. But our interventions are built

on the view that people who miss their court date do not necessarily make an active choice to skip it.

Rather, they may have failed to consider the decision at all due to a number of obstacles. The results

indicate that crime policies that focus on behavioral barriers can oer humane approaches to reduce

negative consequences for both citizens and the criminal justice system, without resorting to the

traditional lever of increasing enforcement.

WITH OLD FORM: 41%

WITH MOST EFFECTIVE

TEXT MESSAGES:

Estimates for summons recipients who provide a phone number

Improvements in timely court appearance

FTA Rates

13%

DECREASE

36%

DECREASE

26%

DECREASE

WITH NEW FORM: 36%

26%

Introduction

T

o bring about behavior change and crime prevention, policymakers within the criminal justice

system have traditionally focused on deterrence. For example, longer prison sentences are often

used to discourage crime by making crimes more costly for oenders.

However, these policies will only be eective if people carefully consider the costs and benefits of

their actions. Yet a growing body of literature in the behavioral sciences suggests that people often

do not think systematically about costs and benefits before acting. Instead, people often base their

decisions on intuitive or automatic processes that falter in predictable ways. Fortunately, the predict-

ability of these processes opens up additional levers for generating behavior change. For example,

behavioral science has shown people will reduce their energy consumption if told how much energy

they use relative to their neighbors

1

or that medical adherence can be boosted with simple reminders

to reduce forgetting.

2

However, insights from behavioral science have yet to be methodically applied

to criminal justice, where they hold promise for making the system fairer and more ecient.

To illustrate this, we focus on one problem: failures to appear in court (FTA). The criminal justice

system cannot work if people fail to appear in court, which is why the system places great weight

on ensuring that people attend required hearings and enforces prescribed responses if they fail to

do so. Nationally, the FTA rate is approximately 21-24% for felony cases.

3

FTA rates for misdemeanor

and low-level oenses are even higher: historically around 40% for summons cases in New York City

(NYC), which in 2014 represented about 130,000 missed court dates. In many jurisdictions, failing to

appear can result in an arrest warrant; in NYC this is the default response in accordance with state

law.

To reduce FTAs, a traditional policy approach would propose stricter enforcement of arrest warrants,

based on the assumption that people skip court because they weren’t deterred by existing penalties.

However, a behavioral science perspective suggests many other factors could lead people to miss

court. For example, they may not have paid close attention to information about their court date when

they got it, they may have simply forgotten, or they may not have planned for taking time o from work

in order to attend their court date. If these behavioral barriers account for some instances of FTA, then

behavioral interventions may help courts reduce FTA rates without resorting to stricter enforcement.

1

Allcott, Hunt, and Sendhil Mullainathan. "Behavior and energy policy." Science 327, no. 5970 (2010): 1204-1205.

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/327/5970/1204

2

Dai, Hengchen, Katherine L. Milkman, John Beshears, James J. Choi, David Laibson, and Brigitte C. Madrian. "Planning prompts

as a means of increasing rates of immunization and preventive screening." Public Policy & Aging Report 22, no. 4 (2012): 16-19.

http://nber.org/aging/roybalcenter/planning_prompts.pdf

3

Cohen, T. H. (2010). Pretrial release of felony defendants in state courts: State court processing statistics, 1990-2004.

https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/prfdsc.pdf

USING BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE TO IMPROVE CRIMINAL JUSTICE OUTCOMES 7Introduction

This policy brief outlines the process and results of a joint project with ideas42 and the University

of Chicago Crime Lab, in partnership with the New York City Mayor’s Oce of Criminal Justice

(MOCJ), New York City Police Department (NYPD), and the New York State Unified Court System

Oce of Courts Administration (OCA). The project’s aim was to develop and test two behavioral

approaches to addressing the common issue of FTA, which plagues court systems across the country.

Instead of applying traditional approaches to increase compliance with court summonses (via stier

enforcement), we looked for opportunities to address contextual factors that were contributing to

missed appearances in NYC courts.

In the following sections, we outline the extent of the FTA problem in NYC, the contextual factors we

identified as contributing to the problem, and two simple, cost-eective solutions we designed and

tested to address it. After presenting results of each intervention, we conclude with thoughts and

recommendations for moving forward.

What is behavioral science?

Behavioral science is the study of how people make decisions and act within a

complex and textured world where details matter. It draws from decades of research

in the social sciences to create a more realistic framework for understanding people.

The standard approach to predicting human behavior suggests that we consider

all available information, weigh the pros and cons of each option, make the best

choice, and then act on it. The behavioral approach suggests something different.

We make decisions with imperfect information and do not always choose what’s

best for us. Seemingly small and inconsequential details undermine our intentions to

act. Behavioral science has been used across a variety of fields to realign policies,

programs, and products with how we really behave in order to improve outcomes.

Behavioral Reasons People

Fail to Appear in Court

C

ourt appearance tickets are issued for low-level oenses, which range from public consumption

of alcohol and public urination to riding a bicycle on the sidewalk and spitting. Among summonses

requiring an in-person court appearance (and were not resolved through plea by mail

4

), historically,

around 40% end in FTA.

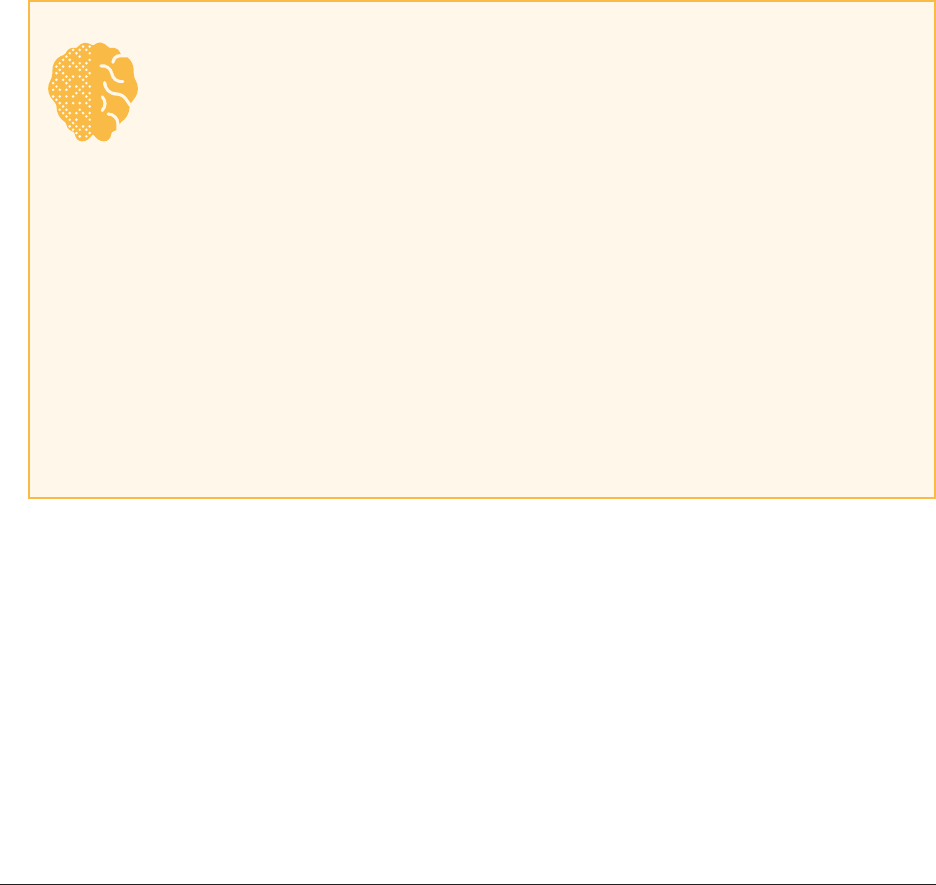

Who Receives Summonses?

Descriptive Statistics of Summons Recipients

5

Summons recipients between January 2016 and June 2017

Borough Oense Past Summons Recipients

24%

29%

20%

22%

5%

8%

6%

8%

25%

10%

34%

9%

32%

68%

First summons

(since January 2012)

Received a prior summons

(since January 2012)

Bronx

Brooklyn

Manhattan

Queens

Staten Island

Alcohol

Park Trespassing Violation

Marijuana

Disorderly Conduct

Public Urination

Motor Vehicle

Other

Gender Breakdown

88%

12%

Male Female

4

The plea by mail option is available for two oenses: public consumption of alcohol and public urination.

5

Source: New York State Unified Court System data

34

years old

Average age

of summons

recipients

USING BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE TO IMPROVE CRIMINAL JUSTICE OUTCOMES 9Behavioral Reasons People Miss Court

In NYC, hundreds of thousands of arrest warrants are currently open due to FTA, which is problematic

for both civilians (who can be taken into custody upon future interaction with police ocers) and for

law enforcement (whose time and resources are spent taking individuals into custody who might

otherwise walk away from interactions with the police). The negative consequences for recipients

could include time in police custody, potential immigration issues, and disruptions to work and family

life—not to mention the psychological costs of worrying about being picked up on an open warrant.

Dealing with these warrants also places a burden on the police and court systems.

To uncover the psychological and contextual features contributing to FTAs, ideas42 and the Crime

Lab conducted quantitative and qualitative research using our behavioral diagnosis methodology.

We uncovered four main barriers contributing to FTAs.

Mental

Models

First, some recipients believe that receiving a ticket for a minor

oense and having to attend court for it is unfair. The crime feels

misaligned with the punishment. That is, having to go to court

for a seemingly minor oense (e.g., being in a park after hours)

doesn’t match with people’s “mental model” of what necessi-

tates a court appearance, much less an arrest warrant.

Present

Bias

Second, the immediate costs of attending court, such as taking

time o work and/or arranging childcare, outweigh the (often

unknown) consequences of not appearing. Many people we

interviewed weren’t aware that a warrant was a consequence

of FTA, but even among those who were aware of the warrant,

some still reported missing court because immediate costs of

going loomed larger than the risk of getting arrested in the future.

This focus on immediate costs over future ones, even when those

future costs are objectively larger, is known as “present bias.”

Social

Norms

Third, there is a misperception about court attendance. A majority

of interviewees hold the misperception that most people do not

attend their court dates, which (consciously or unconsciously)

may influence their own decision to attend or not. Prior work from

behavioral science shows that the perceived behavior of peers

(“social norms”) can have a strong influence on our decisions

and actions.

Inattention

Fourth, the long lag time between receiving the summons and

attending court leads many to forget. In NYC, the court date is

typically 60 to 90 days after the ticket was issued, which is plenty

of time for people to forget about their court date or the summons

altogether. This forgetting can be attributed to “inattention.”

Behavioral Interventions

to Reduce FTA

W

ith our understanding of the contextual and psychological barriers influencing court atten-

dance, we designed two simple, low-cost, scalable solutions to increase appearances.

6

Our

first touch point was the summons form itself, which is the recipients’ main source of information

regarding where and when they must attend court. One reason for FTA could be that people do not

take the time to carefully read the form. We redesigned it to limit the attention needed to acquire the

most important information by putting the essential details near the top of the form and clearly stating

the consequences of missing court.

Comparing the old and new summons form

We made several changes to the recipient copy of the summons form. Some of the main changes of

the front page of the form are described in the call out boxes on the next page.

7

6

These behavioral interventions complement policymaker and judicial system actions to reduce the stock of older open warrants.

Most recently, in August 2017, the Manhattan District Attorney cleared 644,494 warrants dating back at least 10 years.

7

See idea42's website for more details on the form redesign: http://www.ideas42.org/summons

CRC-3206 (5/12)

Name (Last, First, MI)

Street Address

City

ID/License Number

Date of Birth (mm/dd/yy)

Reg State

Time 24 Hour (hh:mm)

Place of Occurrence

In Violation of

Section

VTL

Subsection Admin

Code

Penal

Law

Park

Rules

Other

The Person Described Above is Charged as Follows:

Precinct

Date of Offense (mm/dd/yy) County

Plate Type Veh Type Make Year ColorExpires (mm/dd/yy)

Ht Wt Eyes Hair Plate/Reg

State SexType/Class Expires (mm/dd/yy)

State Zip Code

Apt. No.

Complaint/Information

The People of the State of New York vs.

NYC Pink

Copy

Title of Offense:

Defendant stated in my presence (in substance):

I personally observed the commission of the offense charged herein. False statements made herein are punishable

as a Class A Misdemeanor pursuant to section 210.45 of the Penal Law. Affi rmed under penalty of law.

Complainant’s Full Name Printed Rank/Full Signature of Complainant Date Affi rmed

(mm/dd/yy)

Agency Tax Registry #

The person described above is summoned to appear at NYC Criminal Court

located at:

Command Code

Summons Part County

Date of Appearance (mm/dd/yy)

At 9:30 a.m.

Bronx Criminal Court - 215 E 161

st

Street, Bronx, NY 10451

Kings Criminal Court - 346 Broadway, New York, NY 10013

Redhook Community Justice Center - 88-94 Visitation Place, Brooklyn, NY 11231

New York Criminal Court - 346 Broadway, New York, NY 10013

Midtown Community Court - 314 W 54

th

Street, New York, NY 10019

Queens Criminal Court - 120-55 Queens Boulevard, Kew Gardens, NY 11415

Richmond Criminal Court - 67 Targee Street, Staten Island, NY 10304

DEFENDANT’S COPY

1452220.indd 3 11/25/14 9:29 AM

GLUE LINE

DEFENDANT’S COPY

Criminal Court Appearance Ticket

**To avoid a warrant for your arrest, you must show up to court.**

At court, you may plead guilty or not guilty.

Please see back for exceptions for Public Consumption of Alcohol and Public Urination offenses.

You are Charged as Follows:

Title of Offense:

Time 24 Hour (hh:mm)

Other

VTL

Admin

Code

Penal

Law

Park

Rules

For Additional Information and Questions:

Visit the website or call the number below for additional information about your court

appearance and translation of this document.

www.mysummons.nyc

OR

Call 646-760-3010

County

Date of Offense (mm/dd/yy)

Place of Occurrence

In Violation of Subsection

Section

Show up to court on:

Cell Phone Number (where court may contact you)

Home Phone Number (where court may contact you)

Complainant’s Full Name Printed Rank/Full Signature of Complainant

Date Affirmed

(mm/dd/yy)

Command Code

Defendant stated in my presence (in substance):

(mm/dd/yy)

Court Appearance Date (mm/dd/yy):

at: 9:30 a.m.

Your court appearance location:

Bronx Criminal Court ……………………...……………….. 215 E 161

st

Street, Bronx, NY 10451

Kings & New York Criminal Court ……............ 1 Centre Street, 16

th

Floor, New York, NY 10007

Redhook Community Justice Center ….………......... 88-94 Visitation Place, Brooklyn, NY 11231

Midtown Community Court ………...…………….……. 314 W 54

th

Street, New York, NY 10019

Queens Criminal Court ……………….……. 120-55 Queens Boulevard, Kew Gardens, NY 11415

Richmond Criminal Court …………………………. . sland, NY 1030

Court Locations: You must appear at the court location identified above.

Redhook

Community Justice Center

Bronx

Criminal Court

Kings & New York

Criminal Court

Richmond

Criminal Court

Midtown

Community Court

Other (specify) ______________________________________________

Name (Last, First, MI)

Date of Birth

()

(

)

.

.

.

26 Central Ave, State nI 1..

CRC-3206 (1/16)

Queens

Criminal Court

I personally observed the commission of the offense charged herein. False statements made herein are punishable as a

Class A Misdemeanor pursuant to section 210.45 of the Penal Law. Affirmed under penalty of law.

Precinct

Agency Tax Registry #

2035619.indd 3 1/7/16 10:21 AM

OLD

NEW

USING BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE TO IMPROVE CRIMINAL JUSTICE OUTCOMES 11Behavioral Interventions to Reduce FTA

CRC-3206 (5/12)

Name (Last, First, MI)

Street Address

City

ID/License Number

Date of Birth (mm/dd/yy)

Reg State

Time 24 Hour (hh:mm)

Place of Occurrence

In Violation of

Section

VTL

Subsection Admin

Code

Penal

Law

Park

Rules

Other

The Person Described Above is Charged as Follows:

Precinct

Date of Offense (mm/dd/yy) County

Plate Type Veh Type Make Year ColorExpires (mm/dd/yy)

Ht Wt Eyes Hair Plate/Reg

State SexType/Class Expires (mm/dd/yy)

State Zip Code

Apt. No.

Complaint/Information

The People of the State of New York vs.

NYC Pink

Copy

Title of Offense:

Defendant stated in my presence (in substance):

I personally observed the commission of the offense charged herein. False statements made herein are punishable

as a Class A Misdemeanor pursuant to section 210.45 of the Penal Law. Affi rmed under penalty of law.

Complainant’s Full Name Printed Rank/Full Signature of Complainant Date Affi rmed

(mm/dd/yy)

Agency Tax Registry #

The person described above is summoned to appear at NYC Criminal Court

located at:

Command Code

Summons Part County

Date of Appearance (mm/dd/yy)

At 9:30 a.m.

Bronx Criminal Court - 215 E 161

st

Street, Bronx, NY 10451

Kings Criminal Court - 346 Broadway, New York, NY 10013

Redhook Community Justice Center - 88-94 Visitation Place, Brooklyn, NY 11231

New York Criminal Court - 346 Broadway, New York, NY 10013

Midtown Community Court - 314 W 54

th

Street, New York, NY 10019

Queens Criminal Court - 120-55 Queens Boulevard, Kew Gardens, NY 11415

Richmond Criminal Court - 67 Targee Street, Staten Island, NY 10304

DEFENDANT’S COPY

1452220.indd 3 11/25/14 9:29 AM

GLUE LINE

DEFENDANT’S COPY

Criminal Court Appearance Ticket

**To avoid a warrant for your arrest, you must show up to court.**

At court, you may plead guilty or not guilty.

Please see back for exceptions for Public Consumption of Alcohol and Public Urination offenses.

You are Charged as Follows:

Title of Offense:

Time 24 Hour (hh:mm)

Other

VTL

Admin

Code

Penal

Law

Park

Rules

For Additional Information and Questions:

Visit the website or call the number below for additional information about your court

appearance and translation of this document.

www.mysummons.nyc

OR

Call 646-760-3010

County

Date of Offense (mm/dd/yy)

Place of Occurrence

In Violation of Subsection

Section

Show up to court on:

Cell Phone Number (where court may contact you)

Home Phone Number (where court may contact you)

Complainant’s Full Name Printed Rank/Full Signature of Complainant

Date Affirmed

(mm/dd/yy)

Command Code

Defendant stated in my presence (in substance):

(mm/dd/yy)

Court Appearance Date (mm/dd/yy):

at: 9:30 a.m.

Your court appearance location:

Bronx Criminal Court ……………………...……………….. 215 E 161

st

Street, Bronx, NY 10451

Kings & New York Criminal Court ……............ 1 Centre Street, 16

th

Floor, New York, NY 10007

Redhook Community Justice Center ….………......... 88-94 Visitation Place, Brooklyn, NY 11231

Midtown Community Court ………...…………….……. 314 W 54

th

Street, New York, NY 10019

Queens Criminal Court ……………….……. 120-55 Queens Boulevard, Kew Gardens, NY 11415

Richmond Criminal Court …………………………. . sland, NY 1030

Court Locations:

You must appear at the court location identified above.

Redhook

Community Justice Center

Bronx

Criminal Court

Kings & New York

Criminal Court

Richmond

Criminal Court

Midtown

Community Court

Other (specify) ______________________________________________

Name (Last, First, MI)

Date of Birth

()

(

)

.

.

.

26 Central Ave, State nI 1..

CRC-3206 (1/16)

Queens

Criminal Court

I personally observed the commission of the offense charged herein. False statements made herein are punishable as a

Class A Misdemeanor pursuant to section 210.45 of the Penal Law. Affirmed under penalty of law.

Precinct

Agency Tax Registry #

2035619.indd 3 1/7/16 10:21 AM

1

Clear title describes the purpose and required action.

2

The date, time, and location of the appearance is moved from the bottom to the top, where it is more

likely to be read.

3

The consequence of missing is clearly articulated and framed to spur loss aversion, the human tendency

to feel losses more severely than equivalent gains.

OLD

NEW

1

2

2

3

1

USING BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE TO IMPROVE CRIMINAL JUSTICE OUTCOMES 12Behavioral Interventions to Reduce FTA

The second touch point addressed the lag time between receipt of the summons and the court

date. We designed text message reminders tailored to address the bottlenecks described above.

Compared to other forms of reminders, such as letters or robo-calls, text messages are inexpensive,

and information is easily received and retrievable later.

We designed multiple sets of text messages to determine which messaging is most eective at

reducing FTA. Some were sent before a person’s scheduled court date (pre-court messages) and

some were only sent if they had missed their court date (post-FTA messages). In order to test which

messages were most impactful on FTA rates, recipients were randomly assigned to receive some

combination of pre-court and/or post-FTA messages, or no message at all.

The pre-court message sets consist of three dierent texts, sent seven, three, and one day before

the scheduled court date. This schedule was chosen in order to prompt recipients to take preemptive

action for attending court (i.e. scheduling time away from work or securing childcare) without reminding

them too early, which could lead to procrastination.

Some pre-court messages emphasized the consequences of failing to appear and provided infor-

mation about what to expect at court (“consequences”), while others focused on helping people

develop concrete plans for appearing in court (“plan-making”). A third set combined consequences

and plan-making messages. All messages helped to address inattention or forgetting the court date.

Pre-Court Messages

CONSEQUENCES MESSAGES

7 days before court 3 days before court 1 day before court

Helpful reminder: go to

court Mon Jun 03 9:30AM.

We'll text to help you

remember. [Show up to

avoid an arrest warrant.]

Reply STOP to end texts.

www.mysummons.nyc

Remember, you have

court on Mon Jun 03 at

346 Broadway Manhattan.

[Tickets could be dismissed

or end in a fine (60 days to

pay).] [Missing can lead to

your arrest.]

At court tomorrow at

9:30AM [a public defender

will help you through the

process.] [Resolve your

summons (ID##########)

to avoid an arrest warrant.]

1

Makes the costs of FTA more salient to overcome present bias.

2

Reduces the ambiguity and perceived costs of attending court.

3

Highlights penalties to overcome present bias and the mental model that you don’t need to go

to court for minor violations.

4

Repeats the consequence to keep the cost of missing court top-of mind, reinforcing that despite

the mismatch between crime and punishment, you must attend to avoid a warrant.

1

3

2

2

4

USING BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE TO IMPROVE CRIMINAL JUSTICE OUTCOMES 13Behavioral Interventions to Reduce FTA

PLANMAKING MESSAGES

7 days before court 3 days before court 1 day before court

Helpful reminder: go to

court on Mon Jun 03

9:30AM. [Mark the date on

your calendar and set an

alarm on your phone.] Reply

STOP to end messages.

www.mysummons.nyc

You have court on Mon

Jun 03 at 346 Broadway

Manhattan. [What time

should you leave to get

there by 9:30AM? Any

other arrangements to

make? Write out your plan.]

You have court

tomorrow for summons

ID##########. [Did you

look up directions to 346

Broadway Manhattan?]

Know how you're getting

there? Please arrive by

9:30AM.

1

Encourages people to set reminders to help them remember.

2

Aids people to think ahead and overcome potential barriers (or costs) to showing up to court.

3

Helps plan how to get there and makes the act of going more concrete.

COMBINATION MESSAGES

7 days before court 3 days before court 1 day before court

Helpful reminder: go to

court Mon Jun 03 9:30AM.

We'll text to help you

remember. Show up to

avoid an arrest warrant.

Reply STOP to end texts.

www.mysummons.nyc

You have court on Mon

Jun 03 at 346 Broadway

Manhattan. What time

should you leave to get

there by 9:30AM? Any

other arrangements to

make? Write out your plan.

Remember, you have court

tomorrow at 9:30AM.

Tickets could be dismissed

or end in a fine (60 days

to pay). Missing court for

########## can lead to

your arrest.

These messages, combining elements from both sets above, address present bias,

mental models, and plan-making as previously described.

3

2

1

USING BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE TO IMPROVE CRIMINAL JUSTICE OUTCOMES 14Behavioral Interventions to Reduce FTA

In addition to the pre-court reminders, we developed two types of messages sent only if a person

had missed the court appearance and a warrant had been issued. The first type focused on conse-

quences, letting recipients know that a warrant was issued, but that they wouldn’t be arrested if they

clear it at the court. The second type relied on the power of social norms and informed recipients that

most people actually had attended their court date. Again, both addressed inattention or forgetting.

Post-FTA Messages

CONSEQUENCE MESSAGE

[Since you missed court on

Jun 03 (ID##########),

a warrant was issued.]

[You won’t be arrested

for it if you clear it at 346

Broadway Manhattan.]

www.mysummons.nyc

Sent when a warrant is triggered by an FTA

1

Notifies of the serious consequence that has occurred.

2

Encourages action to resolve the open warrant.

SOCIAL NORMS MESSAGE

[Most people show up to

clear their tickets but records

show you missed court for

yours (ID##########).]

Go to court at 346

Broadway Manhattan.

www.mysummons.nyc

Sent when a warrant is triggered by an FTA

1

Provides feedback that their behavior goes against

the norm.

1

1

2

Results

Solution 1: Summons Form Behavioral Redesign

The redesigned summons form was first introduced to replace old forms in March 2016 and univer-

sally adopted by July 2016. The rollout period culminated in a rapid adoption of the new form across

NYC between June and July 2016. Once the new form was issued citywide, the old forms were

revoked and collected for destruction.

In order to isolate the impact of the redesigned summons form from other contributing factors to

FTA, we compared outcomes between people issued an old form and a new form using a quasi-

experimental approach called a regression discontinuity design. We focused on the narrow time-

window around new form adoption, comparing people who received summonses just before and just

after their issuing ocer switched to the new form. The intuition behind this research design is that

within a few weeks of the switch, the form version a recipient received was as good as random: they

happened to get whichever form the ocer was using at that time. This means that any change in FTA

is likely caused by the new forms.

8

Those who happened to receive the new summons form have an FTA rate that is 13%, or 6.4

percentage points lower than those who happened to receive the old summons form because

their issuing ocer had not switched yet. As the key variable between these two similar groups of

summons recipients, we can determine that the new forms caused this reduction in FTA.

Solution 2: Behavioral Text Messages to Reduce FTA

We evaluated the eect of behavioral text messages using a randomized controlled trial. Anyone in

NYC who was issued a summons and provided their cell phone number was eligible to receive text

message reminders. Summons recipients were randomized to receive one of the pre-court or post-FTA

message sets, or no messages (the “comparison group”). All eects seen here are in addition to the

gains in court attendance already realized through the behavioral summons form redesign.

8

In fact, the characteristics of summons recipients were very similar just before and just after ocers switched forms, in terms of

the kinds of oenses they received summonses for, their age and gender composition, and their likelihood of having received

summonses in the past. Thus, any dierence in FTA rate between those who received the old and new forms would suggest that

the new forms were responsible for the change.

USING BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE TO IMPROVE CRIMINAL JUSTICE OUTCOMES 16Results

TEXT MESSAGE SETS

PRE-COURT MESSAGES

Combination

Messages

Consequences

Messages

Plan-making

Messages

Comparison Group

(No Messages)

1

2

3

1

2

3

1

2

3

If FTA at initial summons court date

POST-FTA MESSAGES

Group A

Consequences

Group B

Consequences

Group C

No Message

Group D

Consequences

Group E

No Message

Group F

Consequences

Group G

Social Norms

Comparison

No Messages

We found that receiving any pre-court message reduces FTA on the court date by 21%. The combi-

nation messages, using elements of both the consequences and plan-making sets, were the most

eective, reducing FTA by 26% (from 38% to 28%). This 26% FTA reduction is measured on the

court date, and comes after receiving the sequence of three pre-court messages.

We also looked at the impact 30 days after the court date, as some summons recipients show up to

court to clear their warrants after their scheduled court date. For the combination messages, when

an individual fails to appear in court, they also receive a post-FTA message. Relative to receiving no

text message, we find a 32% reduction in open warrants for people who received a combination

message set and a post-FTA message (from 24% to 17%). This reflects both the change in FTA

on the court date, as well as subsequent court appearances to clear warrants within 30 days of the

scheduled court date.

There is also a question of whether timing of messages matters for reducing FTA—are messages more

eective when they are sent before missing a court date or after? We find that post-FTA messages

alone are helpful, leading to a 15% reduction in failures to return to court within 30 days, but not

as helpful as pre-court messages. Among post-FTA messages, the consequences message (16%

reduction) was more eective than the social norms message (13.6% reduction).

9

9

We also compared sending just the pre-court messages vs. pre-court plus post-FTA messages. Here, we find that for people who

received pre-FTA messages the eect of receiving an additional post-FTA message is encouragingly in the right direction, but not

yet statistically significant at the typical 5% level.

USING BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE TO IMPROVE CRIMINAL JUSTICE OUTCOMES 17Results

16%

DECREASE

37.8%

31.8%

29%

28.1%

The dierence in FTA rates between the comparison group

and any treatment arm is significant at the 1% level (p<0.01)

0

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

Comparison Group (No Messages)

Plan-Making

Consequences

Combination

24%

DECREASE

26%

DECREASE

CONTROL GROUP A GROUP C GROUP E

19.8%

Pre-Court Plan-Making +

No Post-FTA message

32%

DECREASE

24.3%

The dierence in FTA rates between the comparison group

and any treatment arm is significant at the 1% level (p<0.01)

16.6%

0

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

Comparison Group (No Messages)

Pre-Court Combination +

Post-FTA Consequences

CONTROL GROUP A

20.5%

No Pre-Court Message +

Post-FTA Consequences

GROUP F

17.8%

Pre-Court Consequence +

Post-FTA Consequences

GROUP B

20%

Pre-Court Plan Making +

Post-FTA Consequences

GROUP E

19.2%

Pre-Court Consequence +

No Post-FTA message

GROUP C GROUP D

21%

No Pre-Court Message +

Post-FTA Social Norms

GROUP G

FTA Rate by Type of Message

Open Warrant Rate 30 Days After Court Dates

USING BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE TO IMPROVE CRIMINAL JUSTICE OUTCOMES 18Results

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Both the redesign and text message interventions are inexpensive and scalable. Using the re-designed

form has exactly the same cost as using the old form, and the only cost is incurred during a one-time

change. The text messages are also inexpensive, at less than one cent ($0.0075) per message. For

example, sending all 2014 summons recipients three messages would have cost less than $7,500.

By contrast, the costs of failing to appear in court are much higher. Entry into the criminal justice

system—as would be the case if a person was arrested for having an FTA warrant—can have major

adverse impacts on people’s lives, regardless of the severity of the initial oense. Failures to appear

in court also divert time and resources in both courts and policing. The benefits could be even

larger if these kinds of messages also reduce FTA for more severe oenses, since this could result

in a lesser use of pre-trial detention. By reducing FTA rates,

10

behavioral interventions might make it

possible to allow more people to await trial outside of jail—an important goal for NYC and other U.S.

jurisdictions that are concerned about the racial and social disparities of pre-trial detention. Because

they are so inexpensive and easy to replicate, both interventions could easily be adapted for other

locations and for other types of courts and oenses.

10

Prior failures to appear in court are among the strongest predictors of future missed court appearances, and similarly the most

heavily weighted factors in considering pre-trial release https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/prfdsc.pdf

http://www.nycja.org/lwdcms/doc-view.php?module=reports&module_id=678&doc_name=doc

WARRANTS THAT

COULD HAVE BEEN

AVOIDED IN 2014

20,800-31,300

Total Warrants Avoided Per Year (APPROXIMATE)

3,700-14,300

WARRANTS

AVOIDED

WITH

NO TEXTS

114,100

FTAs

WITH

COMBO TEXTS

110,400

FTAs

13% PHONE COLLECTION

(ACTUAL)

WITH

COMBO TEXTS

99,900

FTAs

50% PHONE COLLECTION

(HYPOTHETICAL)

320,000

scheduled arraignments

41%

FTA RATE

WITH

OLD FORM

131,200

FTAs

WITH

NEW FORM

114,100

FTAs

17,100

WARRANTS

AVOIDED

Next Steps

T

he interventions described here are among the first applications of behavioral science to criminal

justice policy.

11

Promisingly, not only are these solutions impactful, their eects are as large or

larger than some of the most successful similar behavioral interventions in other domains. We see

these interventions as an encouraging first step toward incorporating insights from behavioral science

into criminal justice reform.

An immediate next step is to build o of the results and continue to scale the most eective interven-

tions to reach more people. As a measure of the potential for future growth, a recent survey found that

87% of adults nationwide own a cell phone, with ownership reaching nearly 96% in NYC.

12

While text

messages are very eective, only about 13% of summons recipients in NYC currently provide a cell

phone number, which represents a significant opportunity to expand reach. Enabling more recipients

to get these messages would increase the potential impact of this intervention.

Another promising avenue we are exploring is “personalized reminders.” The usual approach in

behavioral science is to identify the intervention with the largest average eect and administer the

same “nudge” to everyone. We might achieve larger gains by tailoring reminders to individuals, so

that a given individual receives messages specific to the barriers that they are experiencing. For

instance, busy people may be particularly responsive to plan-making messages, while first-time

summons recipients may be more responsive to consequences messages.

Our findings have the potential for impact beyond low-level oenses and beyond NYC. Another

aim is to scale both the redesign of other complex forms that recipients receive and text message

reminders across dierent court systems and cities. Future work could specifically investigate the

gains to behavioral enhancements at criminal courts that handle more serious misdemeanors and

felonies in jurisdictions across the country.

The work we describe here represents an early success in using behavioral science to improve the

criminal justice system. Because behavioral approaches to criminal justice reform have been largely

overlooked, we believe that there are many “easy wins” to be had. Of course, eective nudges are

not substitutes for substantial policy change, but they could be an eective complement and can be

more readily implemented and scaled than broad policy changes. A concerted eort toward low-cost,

incremental benefits could add up to make a significant dierence both for the criminal justice system

and for people’s lives.

This research by ideas42 and the University of Chicago Crime Lab, in collaboration with MOCJ, NYPD,

and OCA, is a promising step toward incorporating behavioral science in criminal justice. We are

eager to continue eorts to better understand how novel, low-cost strategies could be used by NYC

and other jurisdictions to make progress on persistent policy challenges.

11

Another early example is the work of Bornstein et al (2013)." http://ppc.unl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Bornstein-et-al-Re-

ducing-courts-failure-to-appear-rate-by-written-reminders-Psychology-Public-Policy-and-the-Law-2013.pdf

12

https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/dca/MobileServicesStudy/Research-Brief.pdf

USING BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE TO IMPROVE CRIMINAL JUSTICE OUTCOMES 20Next Steps

ideas42 uses the power of behavioral science to design

scalable solutions to some of society’s most difficult problems.

To find out more, visit us at ideas42.org or follow us @ideas42

The Crime Lab partners with policymakers and practitioners to help

cities identify, design, and test the policies and programs with the

greatest potential to reduce crime and improve human lives at scale.

To learn more visit us at urbanlabs.uchicago.edu/labs/crime